Study of Marine Reptile Teeth Hints at Faunal Turnover as Sea Levels Changed

New research undertaken by scientists at Edinburgh University in collaboration with colleagues at the University of Bristol, analysing marine reptile teeth, has revealed that marine faunal turnover during the Jurassic could well reflect what is likely to happen to apex marine predators today, as sea levels rise.

With global warming, so sea levels are likely to rise as ice sheets and glaciers melt. This will have a significant impact on our planet, not least of all for our own species, but scientists are trying to predict the extent of the impact on changing sea levels on marine food chains and ecosystems. Computer modelling can help, but surprisingly, so can studying the fossils of long extinct sea creatures.

Studying Marine Reptile Teeth

Sea levels have risen and fallen on numerous occasions throughout deep geological time. It really is a question of history repeating itself and the scientists writing in the academic journal “Nature: Ecology & Evolution”, report on the study of marine reptile teeth fossils from the Jurassic, which shed light on how reptiles adapted to major environmental changes and how these adaptations might provide a useful metaphor for extant marine life.

The researchers conclude that marine predators that lived in deep waters during the Jurassic Period, thrived as sea levels rose, whilst in contrast, those species that lived in shallower environments, such as near-coastal areas, became extinct.

A Jurassic Marine Ecosystem (Jurassic Sub-Boreal Seaway)

Picture credit: Nikolay Zverkov

The picture (above) depicts a marine ecosystem from the late Middle Jurassic (Callovian faunal stage). A marine crocodile (metriorhynchid crocodyliform) avoids the attention of a large pliosaur attacking a plesiosaur, whilst sharks and a pair of giant, filter feeding Leedsichthys swim nearby. A trio of ammonites can be seen (bottom right).

Marine Food Chains Unchanged for 150 Million Years

The study also indicates that the broad structure of food chains in today’s oceans have remained largely unchanged since the Middle Jurassic. Naturally, the species are very different with mammals taking over the role once occupied by many types of extinct marine reptile, but the underlying structure of the food chain remains similar to what you would have seen had you been scuba diving in the shallow, tropical Jurassic Sub-Boreal Seaway some 160 million years ago.

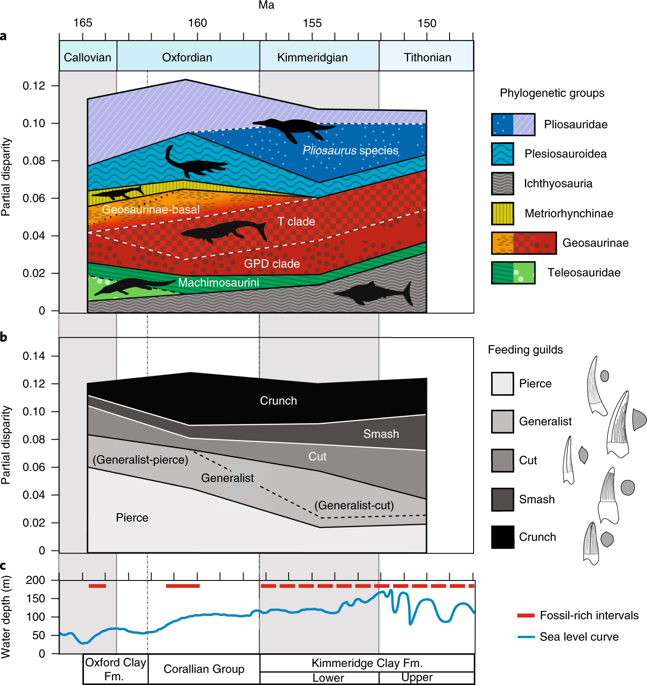

For more than 18 million years, a very diverse, reptile-dominated megafauna co-existed in the Jurassic Sub-Boreal Seaway, a stretch of shallow water that covered present-day northern France to Yorkshire on England’s north-east coast. By examining the shape and size of teeth spanning this 18-million-year period when sea levels fluctuated, the researchers found that species belonged to one of five groups based on their teeth, diet and which part of the ocean they inhabited.

Five Feeding Groups Identified Based on the Shape of Fossil Teeth

The fossil teeth were placed into one of five groups depending on their shape. The shape of the tooth provides a guide to the feeding strategy of the animal and using this data plotted against rising and falling sea levels, the researchers were able to plot how the marine animal populations changed over time as sea levels fluctuated.

The five groups (referred to as feeding guilds), identified were:

- Pierce

- Generalist

- Cut

- Smash

- Crunch

One of the key findings of the study, was that those predators with fine, piercing teeth useful for grabbing fast-moving, slippery prey such as small fish and squid made up a substantial portion of the marine predator population around 165 million years ago (Callovian faunal stage), when sea levels were low and the water relatively shallow. However, as sea levels rose and the sea became much deeper, the teeth of these types of predators were less common in younger rocks dating from around 150 million years ago (Tithonian faunal stage of the Late Jurassic).

Using Fossil Teeth to Map How Marine Apex Predator Populations Changed Over Time

Picture credit: Nature: Ecology & Evolution

The scientists concluded that the pattern that was identified is very similar to the food chain structure of modern oceans, where many different species are able to co-exist in the same area because they do not compete for the same resources. Species used the resources in the environment differently and this permitted them to live together, this is termed niche partitioning.

Niche Partitioning

This niche partitioning enabled many species to co-exist. Although a highly diverse fauna was present throughout the history of the Jurassic Sub-Boreal Seaway, as the scientists studied the teeth found at different stratigraphic levels they found that fish and squid eaters with piercing teeth declined over time while hard-object and large-prey specialists diversified, in concert with rising sea levels.

Larger species that inhabited deeper, open waters began to thrive. These reptiles had broader teeth for crunching and cutting prey. Deep-water species may have flourished as a result of major changes in ocean temperature and chemical make-up that also took place during the period, the researchers postulate. This could have increased levels of nutrients and prey in deep waters, helping the species that lived there. This research provides an analogy for modern ocean environments providing an insight into how species at the top of the marine food chain might respond to rising sea levels brought on by global climate change.

The Fate of Jurassic Predators May Well Provide an Analogy for Modern Marine Ecosystems

Picture credit: Fabio Manucci/University of Edinburgh

The scientific paper: “The Long-term Ecology and Evolution of Marine Reptiles in a Jurassic Seaway” by Davide Foffa, Mark T. Young, Thomas L. Stubbs, Kyle G. Dexter and Stephen L. Brusatte published in the journal Nature: Ecology and Evolution.

The Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment