Articles, features and information which have slightly more scientific content with an emphasis on palaeontology, such as updates on academic papers, published papers etc.

Ancient Whale is Possibly the Heaviest Animal

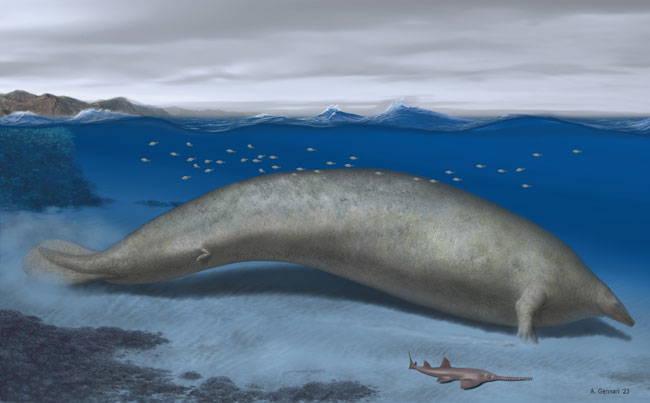

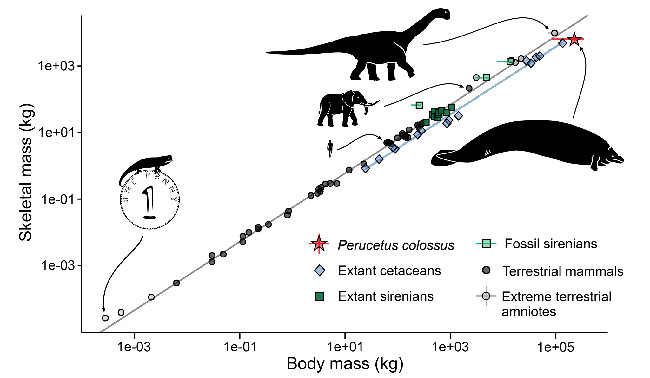

An enormous prehistoric whale named Perucetus colossus might be the heaviest vertebrate to have ever lived. Previously, the heaviest animal known to science was the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus). These whales can weigh up to 190 tonnes. The newly described P. colossus is estimated to have weighed between 85 and 340 tonnes. Researchers writing in the academic journal “Nature” postulate that this animal pushes extreme size in cetaceans to a much earlier phase in their evolutionary development.

Perucetus colossus

Fossils of this leviathan were discovered in the desert on the southern coast of Peru. Palaeontologist Mario Urbina spent decades painstakingly looking for fossils. In 2010, he made an exceptional discovery. Other field team members were puzzled when photographs of the unusual objects jutting out of the 39-million-year-old sediments were examined.

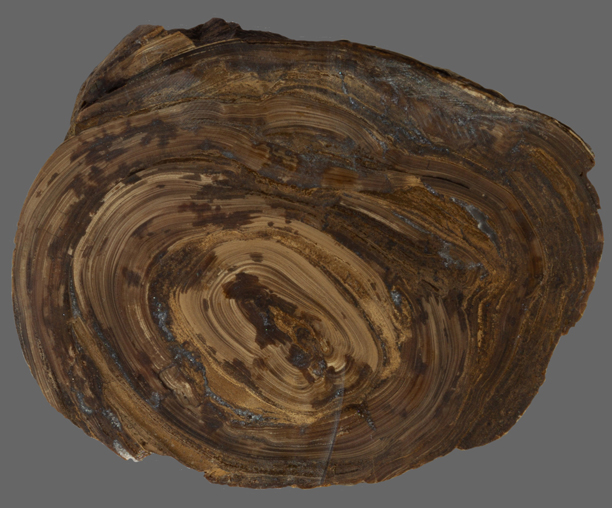

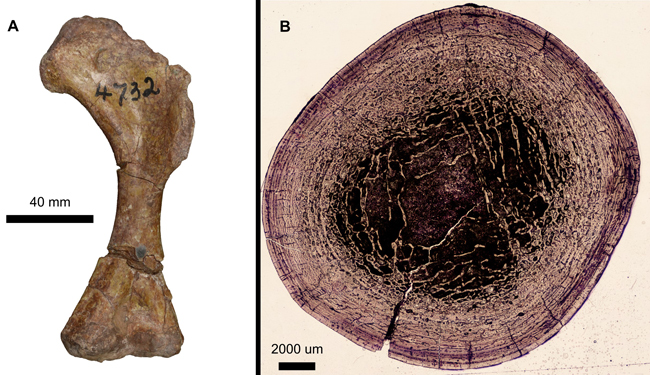

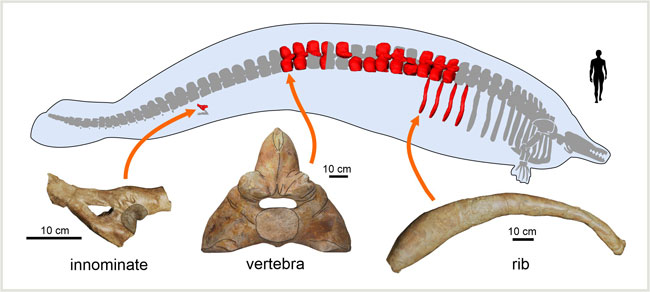

These huge and odd-shaped objects were vertebrae from an immense skeleton. Each bone weighed over a hundred kilograms and four ribs found in association with the thirteen vertebrae measured approximately 1.4 metres in length. Several expeditions had to be organised to excavate and remove the colossal fossils from the remote location.

A New Species of Basilosaurid Whale

The remarkable fossils are now part of the vertebrate collection housed at the Museo de Historia Natural, Universidad Nacional Mayor San Marcos in Peru. Perucetus has been assigned to Basilosauridae family. These whales were the earliest cetaceans to fully transition to an aquatic lifestyle. Basilosaurids are known from the early Eocene to the late Eocene and were geographically widespread.

Perhaps the most famous of all these ancient whales is Basilosaurus. It was an apex predator and some species could have reached lengths of twenty metres or so, approximately the same length as Perucetus colossus, but Basilosaurus was much lighter.

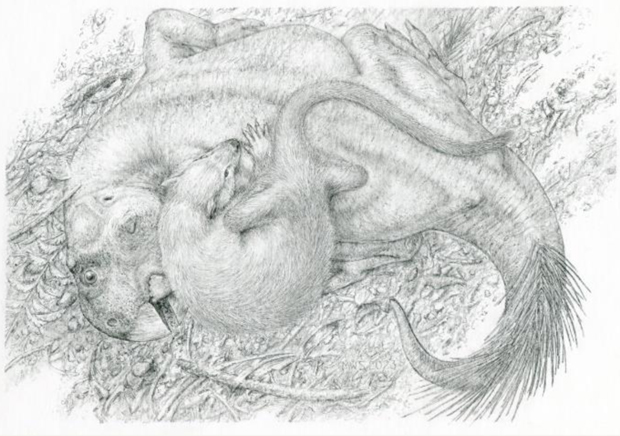

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The picture above depicts a Basilosaurus. Fossils indicate that Basilosaurus was much more slender and serpent-like when compared to the newly described Perucetus. The drawing is based on the CollectA Basilosaurus replica.

To view the not-to-scale CollectA model range: CollectA Age of Dinosaurs Popular Models.

The World’s Heaviest Animal

No other known basilosaurid had such massive bones. An international team of scientists including Olivier Lambert, a palaeontologist at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences surface-scanned the preserved bones to measure their volume. Cores were taken from one dorsal vertebra and a rib to permit an assessment of bone density and structure. Comparisons with extant whales and other extinct basilosaurids were then made.

The twenty-metre-long skeleton of the Perucetus was estimated to be two to three times heavier than the blue whale skeleton called Hope exhibited in the Hintze Hall of the London Natural History Museum. To reconstruct the body mass of Perucetus, the authors used the ratio of soft tissue to skeleton mass known in living marine mammals. With estimates ranging from 85 to 340 tonnes, the mass of Perucetus colossus falls in or exceeds the distribution of the blue whale.

Adapted to a Shallow Water Marine Environment

The scientists postulate that Perucetus was adapted to a shallow water marine environment. The tremendous weight of this cetacean, perhaps as heavy as fifty African elephants, was partly due to modifications observed in the fossil bones. The outer portions of the bones were packed out with additional bone mass, giving them a bloated appearance (pachyostosis). The internal cavities were filled with compact bone (osteosclerosis). These two anatomical traits increased the weight of the skeleton.

Co-author of the study Olivier Lambert commented:

“These modifications are not pathological, but well known in many aquatic mammals (such as manatees) and extinct reptiles who mostly lived in shallow coastal waters. The extra weight helps these animals regulate their buoyancy and trim underwater. A stable position in the water may have been useful when foraging for crustaceans, demersal fish and molluscs along the seafloor. Such a large and heavy animal may also have been able to counteract waves in high-energy waters.”

In extant cetaceans, who can dive at much greater depth and live far offshore, the bone structure is much lighter.

Evidence of Early Gigantism

It had been thought that gigantism in baleen whales was a relatively recent development in cetacean evolution. The first huge filter-feeding whales were thought to have evolved around 5 million years ago (early Pliocene Epoch). However, the discovery of Perucetus colossus pushes back the evolution of gigantism in prehistoric whales to the Eocene.

Olivier Lambert added:

“Discovering a truly giant species such as Perucetus who is affected by strong bone mass increase changes our understanding of whale evolution. Gigantic body masses have been reached 30 million years before previously assumed, and in a coastal context.”

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “A heavyweight early whale pushes the boundaries of vertebrate morphology” by Giovanni Bianucci, Olivier Lambert, Mario Urbina, Marco Merella, Alberto Collareta, Rebecca Bennion, Rodolfo Salas-Gismondi, Aldo Benites-Palomino, Klaas Post, Christian de Muizon, Giulia Bosio, Claudio Di Celma, Elisa Malinverno, Pietro Paolo Pierantoni, Igor Maria Villa and Eli Amson published in Nature.

Visit the award-winning Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.