Fossil finds, new dinosaur discoveries, news and views from the world of palaeontology and other Earth sciences.

A New Pterosaur Species is Described

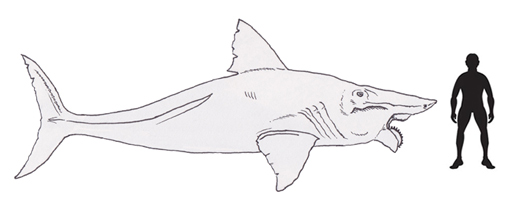

A new pterosaur species has been described based on a superbly preserved specimen found in Upper Jurassic limestone deposits in Bavaria (southern Germany). The fully articulated specimen displays a unique dentition that suggests this flying reptile fed like a modern-day flamingo, sieving water through its jaws to trap small invertebrates as it waded or possibly swam in a shallow lagoon.

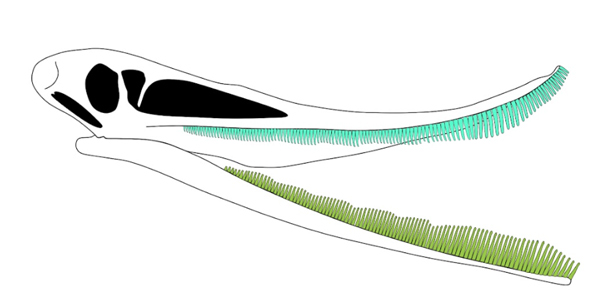

Picture credit: Megan Jacobs

Balaenognathus maeuseri

The pterosaur has been classified as a ctenochasmatid, a group of short-tailed pterodactyloids characterised by specialised teeth adapted for filter feeding. Fossils of these relatively small flying reptiles (most with wingspans less than 3 metres), have been found in Europe, America and China, in rocks dating from the Upper Jurassic to the Early Cretaceous. The new pterosaur has been named Balaenognathus maeuseri, the genus name derives from the scientific name for the Bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus) and the Latin for jaw, as it is thought that these two unrelated species shared a common feeding strategy. The specific epithet honours a co-author of the paper Matthias Mäuser who sadly passed away before publication.

Lead author of the study, published in Paläontologische Zeitschrift (PalZ), Professor David Martill from the University of Portsmouth School of the Environment, Geography and Geosciences commented:

“The nearly complete skeleton was found in a very finely layered limestone that preserves fossils beautifully.”

Unique Pterosaur Dentition

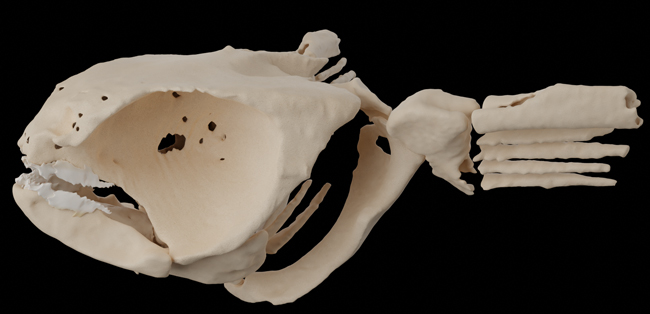

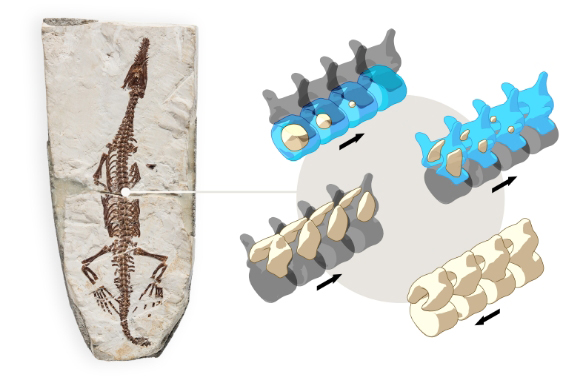

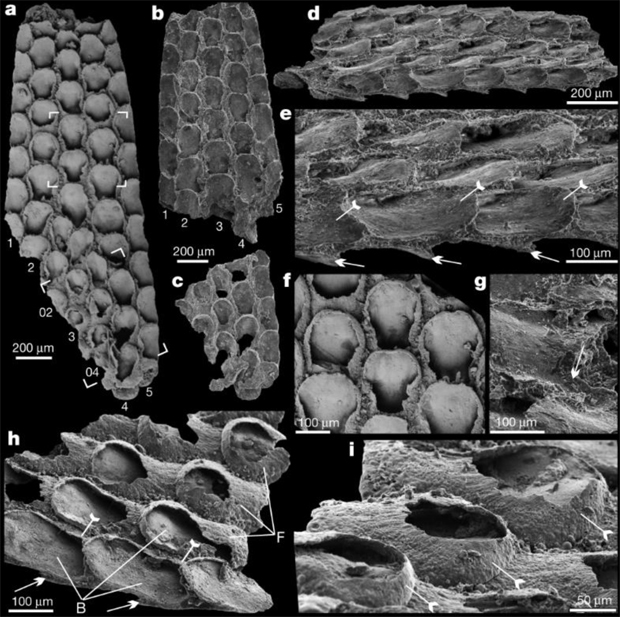

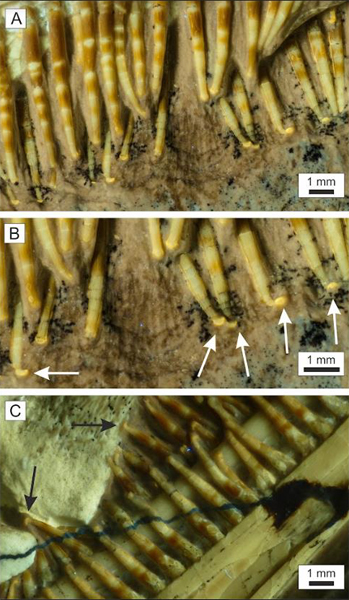

The fossil (specimen number NKMB P2011-63), is remarkable for its completeness, unusual dentition and hints of the preservation of soft tissues, including wing membranes. The delicate jaws contain at least 480 fine teeth.”

Professor Martill added:

“The jaws of this pterosaur are really long and lined with small fine, hooked teeth, with tiny spaces between them like a nit comb. The long jaw is curved upwards like an avocet and at the end it flares out like a spoonbill. There are no teeth at the end of its mouth, but there are teeth all the way along both jaws right to the back of its smile.”

Bizarre Hook-like Tooth Crown

The tips of the jaw are devoid of teeth, which would have permitted plankton and invertebrate-rich water to rush into the long jaw. The hundreds of teeth would have acted as a sieve helping to strain out food. Many of the teeth have a hook-like expansion on the tip of the crown, a bizarre and unique tooth morphology.

Explaining the significance of these strange teeth, Professor Martill stated:

“What’s even more remarkable is some of the teeth have a hook on the end, which we’ve never seen before in a pterosaur ever. These small hooks would have been used to catch the tiny shrimp the pterosaur likely fed on – making sure they went down its throat and weren’t squeezed between the teeth.”

A New Pterosaur

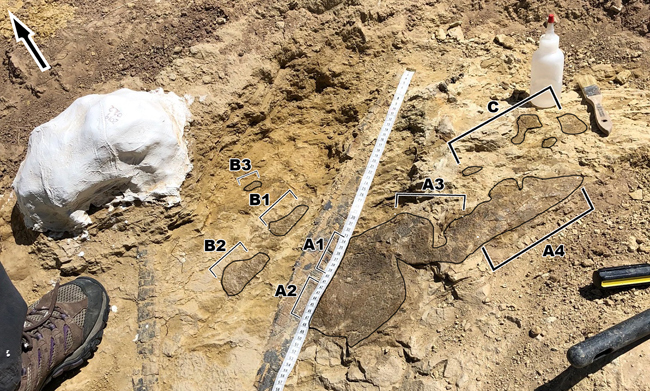

The discovery was made accidentally while scientists were excavating a large block of limestone containing crocodilian fossil remains.

Professor Martill explained:

“This was a rather serendipitous find of a well-preserved skeleton with near perfect articulation, which suggests the carcass must have been at a very early stage of decay with all joints, including their ligaments, still viable. It must have been buried in sediment almost as soon as it had died.”

Most members of the Ctenochasmatidae family seem to have been the pterosaur equivalent of wading shore birds, although some genera were perhaps adapted to habitats further inland and have truly bizarre shaped jaws leaving palaeontologists perplexed as to what they ate.

Only one other known pterosaur had more teeth than Balaenognathus. It is another ctenochasmatid and it is called Pterodaustro guinazui and its fossils are known from the Lower Cretaceous of Argentina. Both Pterodaustro and Balaenognathus were likely filter feeders although the arrangement of their teeth differs. Balaenognathus had teeth in the upper and lower jaw which are the mirror image of each other, whilst P. guinazui had very reduced teeth in the upper jaw and up to a 1,000 densely packed, bristle-like teeth in the lower jaw.

New Pterosaur Species – Unique Feeding Mechanism

The teeth of Balaenognathus suggest a feeding strategy that involved the animal either wading through water or swimming, using its spoon-shaped beak to funnel water into its mouth, this water was then strained through its teeth to trap prey. The researchers propose that Balaenognathus fed on shrimps and copepods filling a similar ecological niche as extant ducks, shorebirds and flamingos.

Commenting on the sad passing of Matthias Mäuser, Professor Martill said:

“Matthias was a friendly and warm-hearted colleague of a kind that can be scarcely found. In order to preserve his memory, we named the pterosaur in his honour.”

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Portsmouth in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper:

The scientific paper: “A new pterodactyloid pterosaur with a unique filter‑feeding apparatus

from the Late Jurassic of Germany” by David M. Martill, Eberhard Frey, Helmut Tischlinger, Matthias Mäuser, Héctor E. Rivera‑Sylva and Steven U. Vidovic published in Paläontologische Zeitschrift (PalZ).