A remarkably well-preserved cranial crest from a pterosaur has provided more evidence that pterosaurs were feathered. Furthermore, analysis of the Tupandactylus specimen (MCT.R.1884), indicates that their bodies were covered with different types of feathers, including branching feathers. The researchers report the presence of different shaped melanosomes associated with the skin and the flying reptile’s feathers. This suggests that pterosaur feathers were not just for thermoregulation, that colouration could be manipulated genetically.

In simple terms, pterosaur feathers probably played a role in visual communication and therefore, visual signalling.

Perhaps feathers evolved independently in the Theropoda and Pterosauria (convergent evolution), if this is not the case, then integumentary coverings originated in the avemetatarsalian ancestor of the pterosaurs and dinosaurs.

Marvellous Melanosomes

Writing in the academic journal “Nature”, the researchers that include University College Cork palaeontologists Dr Aude Cincotta, Professor Maria McNamara and Dr Pascal Godefroit from the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, conclude that pterosaurs were able to control the colour of their feathers using melanin pigments.

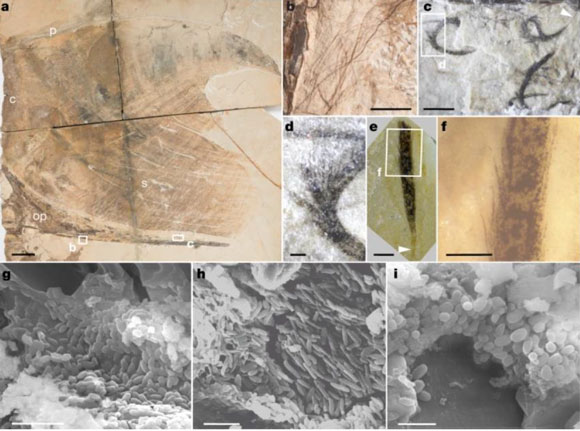

A partial cranium from a Tupandactylus imperator preserved on five limestone slabs from the Lower Cretaceous Crato Formation (Brazil), estimated to be around 115 million years old, was analysed in detail. The scientists discovered that the bottom of the spectacular head crest had a rim of fuzzy feathers, with short wiry hair-like feathers and fluffy branched feathers.

Pterosaur Feather Controversies

Several papers have been published examining integumentary coverings in members of the Pterosauria. It had been established (Yang et al 2018), that flying reptiles had feathery, branched feathers: Are the Feathers About to Fly in the Pterosauria? However, the debate regarding integumentary coverings in pterosaurs is not without controversy.

In 2020, a paper was published that challenged these findings casting doubt on the idea that pterosaurs had an integumentary covering of insulating protofeathers: Naked Pterosaurs – No Feathers Here (Unwin and Martill).

Scanning Electron Microscopes

Soft tissue samples from the cranial crest, simple feathers (monofilaments) and the branching feathers were taken and subjected to scanning electron microscopy. All the samples were found to contain abundant oval-shaped or elongate structures that were interpreted to represent melanosomes. Unexpectedly, the new study shows that the melanosomes in different feather types have different shapes.

Commenting on the significance of this discovery, co-author of the paper, Professor McNamara stated:

“In birds today, feather colour is strongly linked to melanosome shape. Since the pterosaur feather types had different melanosome shapes, these animals must have had the genetic machinery to control the colours of their feathers. This feature is essential for colour patterning and shows that colouration was a critical feature of even the very earliest feathers”.

For models and replicas of pterosaurs and other prehistoric animals: PNSO Museum Quality Prehistoric Animal Models.

Feathers Use in Visual Signalling has Deep Evolutionary Origins

The Pterosauria and the Dinosauria are members of the Avemetatarsalia, a branch of the Archosauria that includes all archosaurs more closely related to birds than to crocodilians. However, the lineage that led to the flying reptiles diverged from the dinosaurs millions of years before birds and feathered dinosaurs evolved. This study also suggests that the function of feathers in visual communication has deep evolutionary origins.

Fossil Repatriated to Brazil

It is also pleasing to note, that thanks to the efforts of the research team, the authorities and other collaborators, this amazing pterosaur fossil that had been in private ownership has been repatriated to Brazil.

Dr Pascal Godefroit (Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences), explained:

“It is so important that scientifically important fossils such as this are returned to their countries of origin and safely conserved for posterity. These fossils can then be made available to scientists for further study and can inspire future generations of scientists through public exhibitions that celebrate our natural heritage”.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a press release from the University College Cork in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Pterosaur melanosomes support signalling functions for early feathers” by Aude Cincotta, Michaël Nicolaï, Hebert Bruno Nascimento Campos, Maria McNamara, Liliana D’Alba, Matthew D. Shawkey, Edio-Ernst Kischlat, Johan Yans, Robert Carleer, François Escuillié and Pascal Godefroit published in the journal Nature.

Visit Everything Dinosaur’s website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment