Research into Fossils Affected by a Significant Colonial Bias

The study of fossils, the science of documenting the history of life on our planet, is heavily biased by influences such as colonialism, history and global economics. That is the conclusion from new research conducted by palaeontologists from the University of Birmingham in collaboration with colleagues from the University of Erlangen-Nürnberg (Germany), Rhodes University (South Africa), Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (Brazil), Cambridge University and IISER Pune, Department of Earth and Climate Science (India).

Distorting Estimates of Past Biodiversity

The research team discovered that sampling biases in the fossil record distort estimates of past biodiversity. However, these biases not only reflect the geological and spatial aspects of the fossil record, but also the historical and current collation of fossil data. These findings have significance across the field of palaeontology, but also for the ways in which researchers are able to use our knowledge of ancient fossil records to gain clearer, long-term perspectives on Earth’s biodiversity.

Writing in the journal “Nature Ecology & Evolution”, the researchers investigated the influence and extent of these biases within the Paleobiology Database, a vast, widely-used and publicly-accessible resource which forms the foundation for analytical studies in the field.

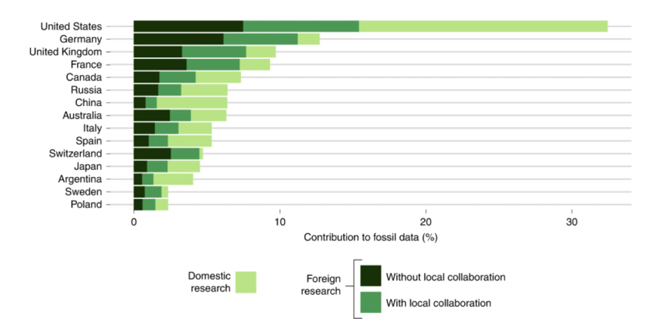

They found significant bias in areas such as knowledge production, with researchers in high or upper-middle-income countries contributing to 97 per cent of fossil data. This means that wealthy countries, primarily located in the Global North control the majority of the palaeontological research power.

Lack of Involvement for Local Researchers

The team also found the top countries contributing to palaeontological research, carried out a disproportionate amount of work abroad, more than half of which did not involve any local researchers (researchers based in the country where the fossils are being collected).

There are many famous examples of colonial, political and economic biases across the natural sciences and humanities. During the 19th century and for most of the 20th century, specimens uncovered following exploratory expeditions were shipped back to respective imperial capitals to be housed in museums, where many are still used for scientific research today.

In a press release from Birmingham University the plight of the Parthenon sculptures, sometimes referred to as the Elgin Marbles was provided as an example. The Greek government has repeatedly requested that they be returned since they were taken from Athens in the early 19th century and transported to Britain.

There are also many other examples, such as the fossil excavations undertaken in Egypt by the German palaeontologist Ernst Freiherr Stromer von Reichenbach or the removal of many Cretaceous-aged dinosaur fossils by French field teams from the island of Madagascar.

Research into Fossils Has a Colonial Bias

The researchers postulate that these biases affect the way in which palaeontologists conduct their research and can lead to unethical practices in the most extreme cases.

Co-lead author Dr Emma Dunne (University of Birmingham) stated:

“Although we know there are these irregularities and gaps in our knowledge of the fossil record, the historical, social and economic factors which influence these gaps are not well understood. Many of the research practices that are informed by these biases still persist today and we ought to be taking action to address them.”

Dr Dunne added:

“We are familiar, for example, with ‘scientific colonialism, or ‘parachute science’, in which researchers, generally from higher income countries drop in to other countries to conduct research, and then leave without any engagement with local communities and local expertise. But this issue goes further than that – the expertise of local researchers is devalued, and laws are often violated, hindering domestic scientific development and leading to mistrust between researchers.”

The first step towards conducting research that is more equitable and ethical, argue the researchers, is to address the power relations driving the production of scientific research. This means properly involving and acknowledging local expertise.

One project which strives to do this is a research project involving researchers from both European and African universities, based in a remote area of Western Cape in South Africa. Here palaeontologists from University of Witwatersrand and the University of Johannesburg are at the forefront of the research and are working with local education specialists Play Africa to create interactive materials that can be toured around schools in the region.

The scientific paper: “Colonial history and global economics distort our understanding of deep-time biodiversity” by Nussaïbah B. Raja, Emma M. Dunne, Aviwe Matiwane, Tasnuva Ming Khan, Paulina S. Nätscher, Aline M. Ghilardi and Devapriya Chattopadhyay published in Nature Ecology & Evolution.