Ancient Placoderm Could Turn Vertebrate Evolution on its Head

Cutting-edge Technology Provides New Insights into Ancient Fish

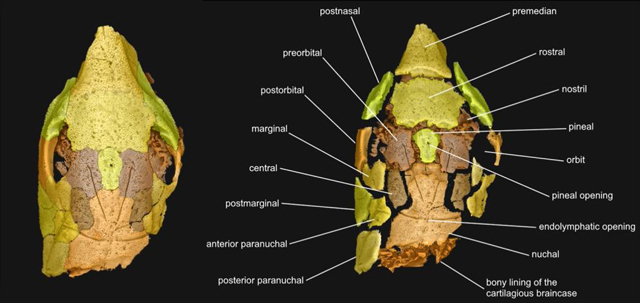

Sophisticated, cutting-edge MicroCT scanning employed to look inside the fossilised skull of a prehistoric fish from the Early Devonian of New South Wales (Australia), has provided scientists with new insights into early vertebrate evolution and challenged the current view regarding the phylogeny and taxonomy of the bony, armoured prehistoric fishes known collectively as placoderms.

The research team, which included scientists from the University of Birmingham, the Chinese Academy of Sciences and colleagues based in Australia and Sweden, used MicroCT scanning to view the internal structures of the skull of a 400 million-year-old Brindabellaspis (Brindabellaspis stensioi) specimen. A fish nicknamed the “platypus fish” due to its elongated snout.

Computer software was used to create a digital reconstruction of brain cavity and the inner ear. The team discovered that Brindabellaspis possessed an inner ear that was surprisingly compact with closely connected components resembling the inner ear of modern jawed vertebrates such as sharks and bony fishes. Some features of the inner ear from this ancient fish are remarkably similar to the structure of our own inner ear.

A Digital Model Showing the Skull and its Constituent Parts (Brindabellaspis stensioi)

Picture credit: Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology

Important Implications for the Placodermi

Brindabellaspis is a member of the Placodermi, a diverse, geographically and temporally widespread class of armoured fish which thrived during the Devonian between 420 and 360 million years ago. Most placoderms have less complex inner ear structures, with a large sac, called a vestibule, placed in the centre and separating all the other components. The remarkably well-preserved and three-dimensional nature of the specimens from New South Wales provided the research team with an opportunity to examine the brain cavity and inner ear of Brindabellaspis for the first time.

Their findings could change the way in which the tree of life representing early vertebrates is constructed.

Life Reconstruction of a Devonian fish – The Giant Placoderm Dunkleosteus

The picture above shows a replica of Dunkleosteus, a giant placoderm. The model is from the PNSO range of figures.

To view this range: PNSO Prehistoric Animal Models.

Re-writing the Evolutionary History of Early Vertebrates

Previous studies had suggested that prehistoric fish such as Brindabellaspis were closely related to primitive, jawless fish (agnathans), that first evolved around 500 million years ago. This study challenges the assumption that placoderms are a distinct group, as considerable variation has been identified in the brain cavities and inner ears of “placoderms”.

Furthermore, this research suggests the possibility that these types of fish may be the ancestors of modern jawed vertebrates (the Gnathostomata).

Co-author of the scientific paper, published in the journal Current Biology, Dr Sam Giles (University of Birmingham), stated:

“The inner ear structure is so delicate and fragile that it is rarely preserved in fossils, so being able to use these new techniques to re-examine specimens and discover this wealth of new information is very exciting. This fossil has revealed a really intriguing mosaic of primitive features and a surprisingly modern inner ear. We don’t yet know for certain what this means in terms of our understanding of how modern jawed vertebrates evolved, but it’s likely that virtual anatomy techniques are going to be a critical tool for piecing together this fascinating jigsaw puzzle.”

Sensitive Snouts

An earlier research paper suggested that the snout of Brindabellaspis was sensitive and may have played a role in locating food or avoiding predators. To read Everything Dinosaur’s article from 2018 about this study: A Primitive Placoderm Platypus Fish from Australia.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Birmingham in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Endocast and Bony Labyrinth of a Devonian “Placoderm” Challenges Stem Gnathostome Phylogeny” by You-an Zhu, Sam Giles, Gavin C. Young, Yuzhi Hu, Mohamed Bazzi, Per E. Ahlberg, Min Zhu and Jing Lu published in Current Biology.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.