New Study Reveals Oldest Evidence of Megapredation

Triassic Ichthyosaur Bit Off More than it Could Chew

An international team of researchers have reported the oldest evidence found to date of megapredation, that is, when one large predator eats another large animal. Sadly, for the 4.8 metre ichthyosaur at the centre of this research published in the on-line, open access journal iScience, the victim, a 4-metre-long thalattosaur (another type of marine reptile), turned out to be the last meal this fish lizard ever had.

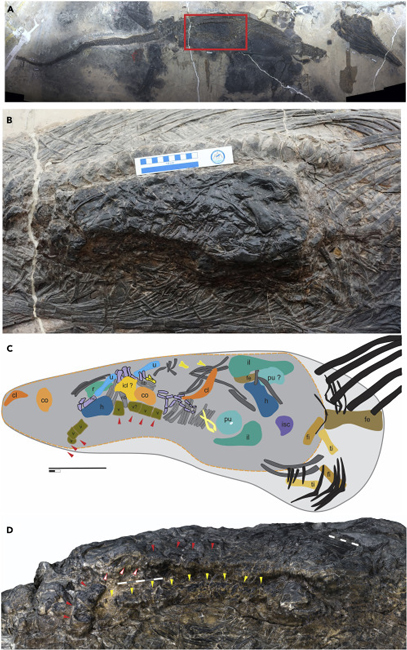

Evidence of Megapredation – Thalattosaur Torso Found in Stomach of an Ichthyosaur

Picture credit: Jiang et al/iScience

Which Marine Reptiles were Top of the Food Chain?

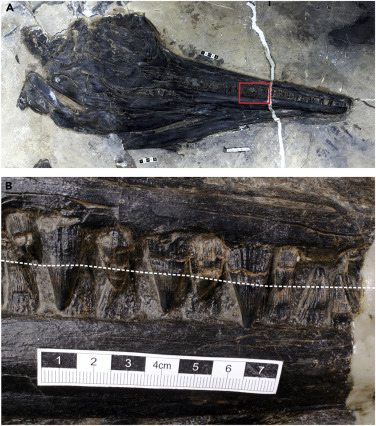

When it comes to mapping Mesozoic food chains it is how big the animal was and the size and shape of the teeth that are usually used to determine position in the food web. Large animals with big, pointed teeth are usually regarded as the apex predators. However, there is little direct evidence in terms of stomach contents to support these assertions.

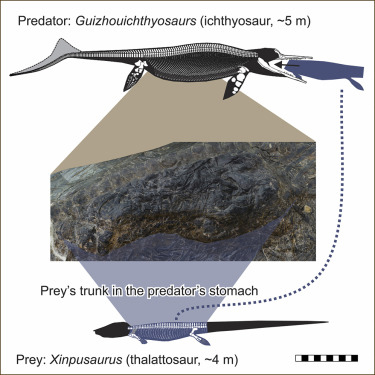

A nearly complete specimen of a Guizhouichthyosaurus has been found that contained the torso of another marine reptile, nearly as big as the ichthyosaur. Guizhouichthyosaurus is believed to have reached a length of between 6-7 metres (most specimens are much smaller). Their teeth are not huge and they seem adapted to grabbing slippery prey such as fish and squid. However, the evidence is quite compelling, it seems that Guizhouichthyosaurus also fed on other large marine reptiles too. Until this fossil discovery, Guizhouichthyosaurus had not been regarded as an apex predator.

Specimen of Guizhouichthyosaurus with Stomach Contents

Picture credit: Jiang et al/iScience

A Surprise in the Abdominal Region

The ichthyosaur specimen, likely to represent a new species of Guizhouichthyosaurus was found in 2010 and excavated from the Ladinian (Middle Triassic) Zhuganpo Member of the Falang Formation in Xingyi, Guizhou Province, in south-western China. During preparation, a large block of bones was identified in the stomach cavity. It soon became clear that these bones were not from the ichthyosaur but represented a thalattosaur, identified as Xinpusaurus xingyiensis.

The seventy-four centimetre mass was classified as a bromalite, a trace fossil representing the remains of material sourced from the digestive tract of the ichthyosaur. The lack of evidence of damage from stomach acids suggests that the unfortunate Xinpusaurus had been swallowed shortly before the Guizhouichthyosaurus itself died. Attempting to consume such a large item of prey probably killed the ichthyosaur.

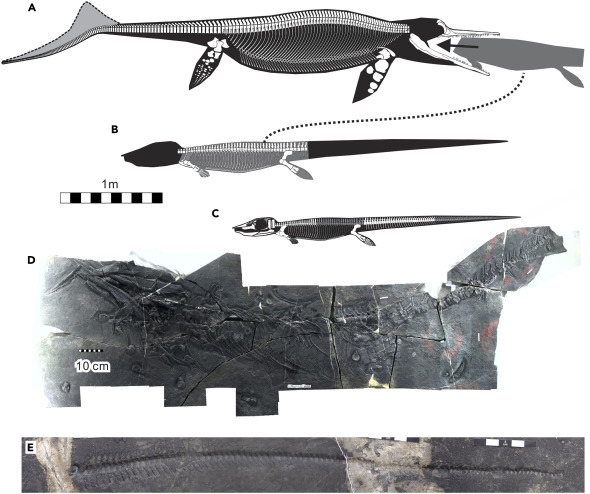

Skeletal Reconstruction of the Ichthyosaur and Thalattosaur

Picture credit: Jiang et al/iScience

Scavenging a Carcase Discounted

An articulated Xinpusaurus tail was found some twenty-three metres away from the ichthyosaur/thalattosaur specimen. Whilst it is not possible to definitively match this tail to the bromalite, the researchers suggest that the tail could have come from the prey. The presence of limb bones in the stomach cavity indicate that the Xinpusaurus was attacked and that the ichthyosaur was not scavenging a carcase. If the Guizhouichthyosaurus had been feeding on a rotting corpse, it is likely that the Xinpusaurus limb bones would have become detached from the body as the soft tissue eroded.

It has been proposed that the ichthyosaur attacked the slightly smaller Xinpusaurus at the water’s surface. The predator employed a “grip and tear” strategy, as seen in extant aquatic predators such as large crocodilians and killer whales (Orcinus orca). By grabbing the victim and thrashing its powerful body and tail, the Xinpusaurus could have been ripped to pieces by the ichthyosaur. This might explain why the head and neck of the Xinpusaurus is missing whilst a detached tail was found nearby.

The Skull of the Guizhouichthyosaurus and a Close View of the Teeth

Picture credit: Jiang et al/iScience

Guizhouichthyosaurus Fossil Study

The remarkable fossils most likely represent the oldest record of megafaunal predation by a marine reptile and the oldest example of megapredation. If Guizhouichthyosaurus was capable of such carnage then it seems the many more Mesozoic reptiles, not previously considered as top predators could also have indulged in megapredatory behaviour.

The scientific paper: “Evidence Supporting Predation of 4-m Marine Reptile by Triassic Megapredator” by Da-Yong Jiang, Ryosuke Motani, Andrea Tintori, Olivier Rieppel, Cheng Ji, Min Zhou, Xue Wang, Hao Lu and Zhi-Guang Li published in iScience.

The Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.