Thin-skinned, Grey Duck-billed Dinosaurs

Scientists writing in the journal of The Palaeontological Association have published a remarkable study on the properties of the skin of duck-billed dinosaurs. Analysis of fossilised hadrosaur skin, from the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History (New Haven, Connecticut), suggests that the skin structure of these dinosaurs had more in common with living birds than with reptiles. In addition, the skin is much thinner when compared to large, terrestrial mammals of comparable size such as elephants and rhinos.

In a blow to palaeoartists who like to adorn their ornithischian illustrations with a multitude of colours, the scientists conclude from an analysis of potential preserved skin pigments that hadrosaurids were grey in colour.

Hadrosaurs Could Have Been Largely Grey in Colour Just Like Big Terrestrial Mammals Alive Today Such as Elephants

The picture (above) shows a Gryposaurus from the Wild Safari Prehistoric World series.

To view this range: Wild Safari Prehistoric World Models.

Getting Under the Skin of Duck-billed Dinosaurs

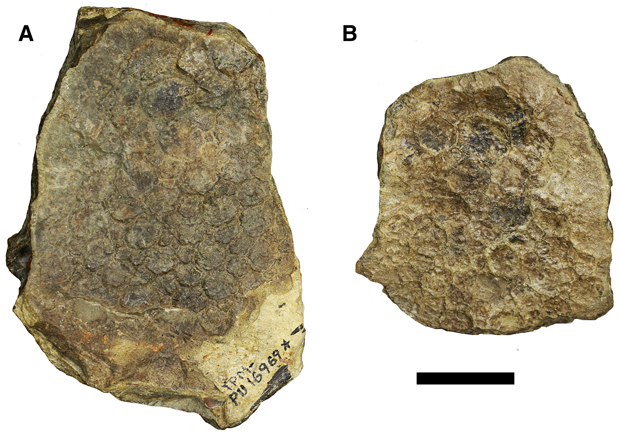

Scientists from Yale University, in collaboration with colleagues in Italy, investigated the chemical properties of a section of fossilised duck-billed dinosaur skin that had been preserved in three dimensions. The specimen (YPMPU 016969) was also subjected to detailed chemical mapping and microspectroscopy as well as scanning electron micrographs to establish the anatomical structure.

Two of the three layers associated with skin in tetrapods were identified, the outer layer (epidermis) and the dermis. The innermost layer, the subcutis, could not be identified in this study. The dinosaur’s scales on the skin surface are very well-preserved. They form an irregular, pebbly pattern with individual scales ranging in size from under one millimetre in diameter to much larger scales around 12 millimetres across.

Specimen Number YPMPU 016969 – The Fossilised Skin Studied

Picture credit: Yale University

Three-dimensionally Preserved Pigment Bearing Bodies and Blood Vessels

The detailed analysis of the fossilised skin and the samples taken permitted the scientists to identify three-dimensionally preserved eumelanin‐bearing bodies. This enabled the researchers to propose that the dinosaur was mostly dark grey in colour, a skin colouration that reflects ecological parallels seen in today’s large, terrestrial animals such as elephants and rhinos. However, caution is urged when it comes to determining the colouration of these types of dinosaurs.

There might be a preservation bias in favour of pigment cells that produce darker skin tones, other pigments may not have been preserved. The section of fossil skin also permitted the researchers to trace blood vessels and dermal cells.

The Study Suggests That Large-bodied Hadrosaurids Were Similar in Colour to Today’s Large-bodied Terrestrial Mammals

Picture credit: Yale University

Surprisingly Thin Skin

The skin was found to be much thinner than that of living mammals of similar size. The outer layer of skin is around 0.2 mm in thickness, whilst the dermis is estimated to have been up to 3 mm thick. Although, no measurements for the subcutis layer could be made, in living elephants the skin is around 10-15 mm thick and in extant rhinos a skin thickness (all three layers, epidermis, dermis and subcutis), of 25 mm is not uncommon.

The relative thickness of the epidermis and dermis in YPMPU 016969 resembles that in birds more closely than that of reptiles.

If the skin of these large, Cretaceous herbivores is so much thinner than previously thought, then how does it fossilise more readily than the integumentary coverings of other dinosaurs? After all, the most commonly preserved soft tissues associated with ornithischian dinosaurs are skin remains. The researchers postulate that the unusual layering and the microstructure of hadrosaur skin may play an important role in its fossilisation potential.

The scientific paper: “Three-dimensional soft tissue preservation revealed in the skin of a non-avian dinosaur” by Matteo Fabbri, Jasmina Wiemann, Fabio Manucci and Derek E. G. Briggs published in Palaeontology – the journal of The Palaeontological Association.

The Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment