Eofringillirostrum boudreauxi and Eofringillirostrum parvulum Passerines from the Early Eocene

A scientific paper has just been published in the journal “Current Biology”, that describes two Early Eocene, seed-eating, perching birds (passerines). The birds are closely related, assigned to the same genus but one fossil was discovered in Wyoming, the other comes from the famous Messel shales of Germany and they are separated by around 5 million years. These species are amongst the oldest fossil birds to exhibit a finch-like beak and provide the earliest evidence for a diet focused on small, hard seeds in crown birds.

The discovery of these two early granivores, will help scientists to better understand the evolution and radiation of this important group of birds, that make up 65% of all extant bird species.

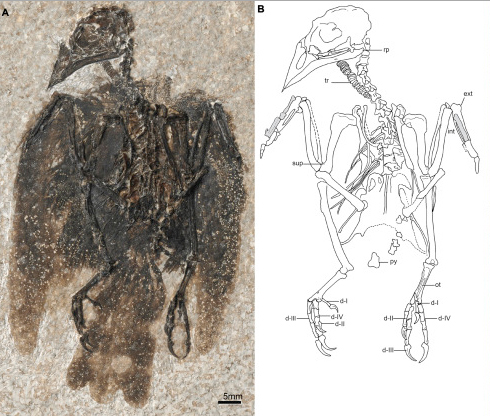

The Wyoming Specimen – Holotype of Eofringillirostrum boudreauxi

Picture credit: Current Biology

The Ancestors of Sparrows, Finches, Crows, Robins etc.

Passerines might be ubiquitous these days, but once they were rare and only made up a small proportion of avian biotas. We still have a lot to learn about their evolution.

Commenting on the significance of the fossil discoveries, one of the co-authors of the paper Lance Grande (Field Museum, Chicago), stated:

“This [Eofringillirostrum boudreauxi] is one of the earliest known perching birds. It’s fascinating because passerines today make up most of all bird species, but they were extremely rare back then. This particular piece is just exquisite. It is a complete skeleton with the feathers still attached, which is extremely rare in the fossil record of birds.”

The Wyoming specimen, E. boudreauxi, is the earliest example of a bird with a finch-like beak, similar to many of the birds you see today inhabiting parks and gardens. This legacy is reflected in its name; Eofringillirostrum means “dawn finch beak”, whilst the specific epithet honours Terry and Gail Boudreaux, who donated the holotype to the Field Museum.

The Green River Formation

The Wyoming specimen heralds from the famous Early Eocene Green River Formation, extensive fine-grained deposits formed in a lacustrine environment. The area is famous for its beautifully preserved but compressed vertebrate fossil specimens.

Lead author of the research, Daniel Ksepka from the Bruce Museum (Connecticut), commented on the importance of finding fossil birds with finch-like beaks adapted to eating seeds:

“These bills are particularly well-suited for consuming small, hard seeds. Anyone with a birdfeeder knows that lots of birds are nuts for seeds, but seed-eating is a fairly recent biological phenomenon.”

The earliest birds probably ate insects, plant material and even fish, although a recent theory has been proposed that the ability to consume seeds may have helped some kinds of birds survive the catastrophic end-Cretaceous mass extinction event.

To read an article about this: Seed-eating may have Helped Birds Survive Mass Extinction Event.

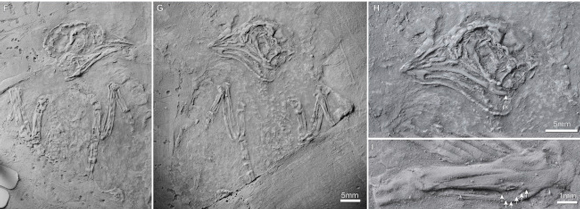

Comparing the Two Fossils

Both the Wyoming and the German specimens have similar shaped beaks, although the German fossil represents a slightly smaller type of bird. Beak shape infers information about the bird’s diet and as such, beak shape plays a key role in avian radiations and is one of the most intensely studied aspects of avian evolution and ecology.

With two specimens that were both temporally and geographically dispersed the researchers were able to conclude that these types of birds were widespread during the Eocene.

The Messel Shale Passerine Specimen – Eofringillirostrum parvulum

Picture credit: Current Biology

Found in Subtropical Habitats Not Open Plains

Whilst many Passeriformes (passerines or perching birds), are synonymous with open, grassland environments today, the researchers note that these fossil specimens occurred in subtropical palaeoenvironments. Given that seed-eating (granivory), is a key adaptation that allows passerines to exploit open temperate environments, the seed-eating habit may have evolved prior to the movement of these types of birds into more open habitats. The ability to consume and digest seeds may not have been a driver in allowing these types of birds to exploit new habitats, but this type of feeding behaviour would have proved to be extremely beneficial as the world became much cooler towards the end of Eocene and the once widespread rainforests gave way to more open landscapes.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a press release from the Field Museum (Chicago), in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Oldest Finch-beaked Birds Reveal Parallel Ecological Radiations in the Earliest Evolution of Passerines” by Daniel T. Ksepka, Lance Grande and Gerald Mayr published in Current Biology.

Visit the customer-friendly Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment