Was There Life on Land During the Ediacaran?

The transition of vertebrates from fully aquatic to partially terrestrial animals has been well documented. Transitional vertebrates such as the remarkable Tiktaalik roseae* provide evidence of the anatomical adaptations undertaken by back-boned animals as they conquered the land. However, invertebrates got there first and before them the land was home to other organisms such as multi-cellular, photosynthesisng mats of algae. When complex organisms, rather than members of the Plantae Kingdom or bacteria established themselves on land is somewhat controversial, but new clues might be emerging from fossils found in some of the oldest known soils on Earth. Could land-dwelling organisms have been present during the Ediacaran?

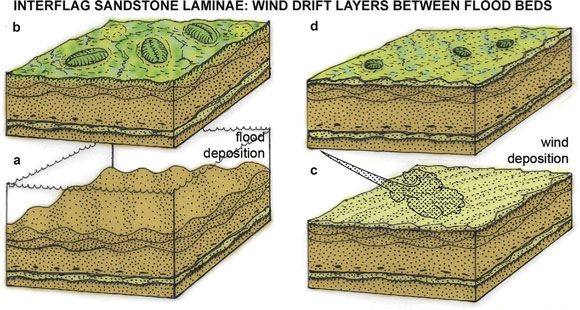

An Ediacaran Fossil Affected by Wind-drift Deposition

Picture credit: Greg Retallack (Oregon University)

Not Marine Fossils But Fossils from a Fluvial Environment

Multi-cellular, terrestrial animals may have existed during the Ediacaran, that is the conclusion of Greg Retallack, fossil collections director at the University of Oregon’s Museum of Natural and Cultural History, writing in the journal Sedimentary Geology. The evidence for such a conclusion emerged from fossil assemblages, previously considered to represent ocean organisms, found in thin layers of silt and sand located between thicker sandstone beds from Ediacaran-aged fossil localities of Nilpena, South Australia and in similarly aged rocks from Namibia.

The Ediacaran is the last geological period of the Precambrian (Neoproterozoic Era), it lasted from 635 million years ago to 542 million years ago and this period in Earth’s history was named after the Ediacara Hills, located north of Adelaide (South Australia), in which, geologist Reginald Sprigg discovered a remarkable collection of fossils representing bizarre, soft-bodied organisms.

Commenting on his new research Greg Retallack stated:

“These Ediacaran organisms are one of the enduring mysteris of the fossil record. Were they worms, sea jellies, sea pens, amoebae, algae? They are notoriously difficult to classify, but conventional wisdom has long held that they were marine organisms.”

Studying Interflag Sandstone Laminae

An in-depth, microscopic analysis of the sediments and their geochemical properties has led to a reassessment of the environmental conditions that led to their deposition. The grains that make up the sediments, reveal telltale marks of ancient wind erosion, the sediments suggest wind-drift deposition between flood beds. This indicates a terrestrial origin for them and not deposition in a marine environment, after all, wind (aeolian forces), hardly affect sand grains on the seabed.

These thin, silty to sandy layers that are “sandwiched” between thicker sandstone beds are referred to as interflag sandstone laminae, they are sometimes called “shims” or “microbial mat sandwiches”. In the research paper, Greg Retallack found similar structures in modern river deposits as well as more ancient interflag sandstone laminae in Pennsylvanian (Upper Carboniferous), and Eocene fluvial levee facies.

Thin, Silty to Sandy Layers Deposited Between Thicker Layers of Sandstone

Picture Credit: Greg Retallack (Oregon University)

Professor Retallack confirmed his diagnosis of an aeolian factor in the deposition by stating:

“Such wind-drifted layers are widespread on river levees and sandbars today. They are present throughout the Flinders Ranges of South Australia and also in Ediacaran rocks of southern Namibia.”

If the sediments are affected by aeolian forces, then it follows that they were deposited in terrestrial environments and therefore the fossil assemblage associated with these deposits are very likely to represent a terrestrial biota. The organisms that left these fossils would have been multicellular and quite complex, visible to the naked eye. Such life would have preceded the emergence of the first land plants by many tens of millions of years.

Unearthing Important Clues

The Ediacaran biota remains extremely difficult to classify, only impressions have been preserved so the internal structure of most of these bizarre organisms is entirely unknown. They could represent a “dead-end” in the evolution of complex life, or some of them might be ancestral to extant groups of animals. The fauna of the Ediacaran might remain enigmatic, when it comes to learning what the fossils actually represent, but this new study offers some intriguing new evidence about the palaeoenvironment.

The Professor concluded:

“The investigation points to a terrestrial habitat for some of these organisms, and combined with growing evidence from studies of fossil soils and biological soil crust features, it suggests that they may have been land creatures such as lichens.”

*To read an article about Tiktaalik roseae: Scientists Get to Grips with Tiktaalik’s Rear End.

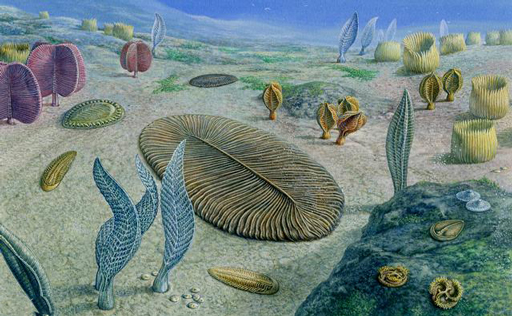

Life in the Ediacaran (Marine Biota)

Picture credit: John Sibbick

The scientific paper: “Interflag Sandstone Laminae, A Novel Sedimentary Structure, with Implications for Ediacaran Paleoenvironments” by Gregory J. Retallack published in Sedimentary Geology.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the help of a press release from the Univesity of Oregon in the compilation of this article.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment