Soft-tissue Evidence for Warm-blooded Ichthyosaurs

The fossilised remains of a beautifully-preserved ichthyosaur fossil from the Lower Cretaceous of Germany has revealed that “fish lizards” had blubber just like many modern, mammalian marine animals. In addition, the fossil is so well-preserved that some of the soft-tissue associated with the specimen have retained some of their original pliability. The fossil is an example of Stenopterygius, (MH 432; Urweltmuseum Hauff, Holzmaden, Germany) and it demonstrates aspects of convergent evolution showing how ichthyosaurs adapted to a marine environment in remarkably similar ways to what is seen in modern cetaceans.

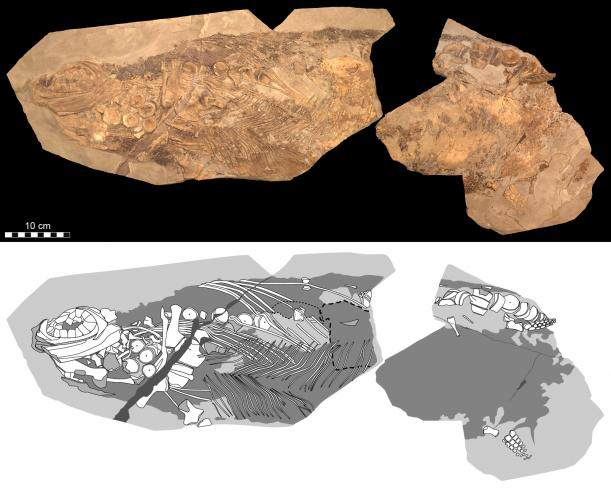

Specimen Number MH 432 – The Partial Skeleton of a Stenopterygius Ichthyosaur with an Accompanying Line Drawing

Picture credit: Johan Lindgren

The marine reptile lived in what is southern Germany today, during the Jurassic Period approximately 180 million years ago. At that time, the reptile, which was probably around two to three metres in length, swam in a vast, shallow ocean that was then covering large parts of present-day Europe.

Johan Lindgren, a senior lecturer in the Department of Geology (Lund University, Sweden), led the international collaboration that resulted in the most comprehensive and in-depth examination of a soft-tissue fossil ever undertaken. Among other things, the study revealed that the soft parts had fossilised so rapidly that both the original cells and their internal contents were preserved.

The international research team identified blubber under the smooth skin that lacked scales. Traces of internal organs were also analysed.

Dr Lindgren observed:

“You can clearly see both the body outline and remains of internal organs. We can even distinguish the different cellular layers within the skin.”

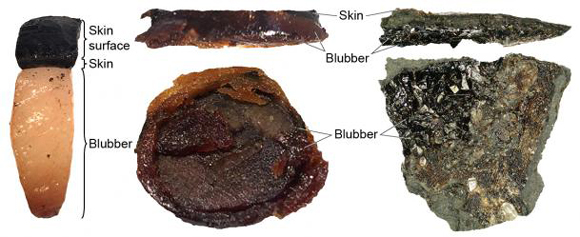

Finding Evidence of Blubber Under the Skin

The researchers identified blubber underneath the skin. To date, such specialised fat-laden tissue has only been found in modern marine mammals and adult individuals of the Leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelyidae coriacea). The discovery of blubber suggests that ichthyosaurs had metabolic rates that were higher than those of typical extant reptiles. It suggests a degree of homeothermy in the Ichthyosauria. In essence, these reptiles were able to sustain an internal body temperature regardless of how cold the water was they were swimming in.

The results from this study could help to explain why the Ichthyosauria had such a large geographical range during the Mesozoic. These creatures, that first evolved in the Triassic and died out some 80 million years ago, had an almost global distribution, even in cold waters. Their layer of blubber would have helped them to dive very deep, perhaps diving to the deepest parts of the Epipelagic zone of the ocean or even into the Mesopelagic zone (diving down more than 220 metres).

Comparing Pressure and Heat Treated Porpoise Blubber to Ichthyosaur Fossil Blubber

Picture credit: Johan Lindgren and Martin Jarenmark

The team of international scientists also examined remains of the animal’s liver, which included part of the original biochemistry (eumelanin pigment and haemoglobin residues).

Dr Lindgren stated:

“It’s truly remarkable that the biomolecules we discovered so closely match the tissues that we could identify.”

In the study, the researchers also succeeded in showing that the fossil contains tissues that still retain some of their original pliability, even though 180 million years have passed since the animal died and sank to the bottom of the sea. The team used chemicals to remove the mineral phase of the specimen, the inorganics that once turned the animal carcass into a petrified fossil. Subsequent tests revealed that the soft tissues still retained a degree of elasticity.

Ichthyosaurs Had Counter Shading

A study of the melanophores and their distribution across the body indicates that ichthyosaurs possessed countershading. They were darker on top, but lighter underneath. The upper part of the body was dark, this may have helped the animal to warm up rapidly at the surface after a deep dive. The dark colouration would absorb more energy from the sun. In addition, the dark upper part of the body would provide a degree of UV protection and the countershading would have provided effective camouflage. Many, living large pelagic (actively swimming), animals exhibit countershading.

A Model of an Ichthyosaur Showing Countershading

The model (above) is from the Safari Ltd range of figures.

To view this range of models: Wild Safari Prehistoric World Models.

Identifying Pigment Cells (Melanophores) in Fossil Material

Picture credit: Mats E. Eriksson, Federica Marone and Ola Gustafsson

Improving our Knowledge of Taphonomy

The research team conclude that this fossil has provided some remarkable insights into ichthyosaur anatomy and biology. The study also reveals how much more we have to learn about the process of fossilisation (taphonomy). The beautifully-preserved Stenopterygius fossil demonstrates a number of adaptations that ichthyosaurs share with other, living marine creatures such as the Leatherback turtle and toothed whales such as dolphins and porpoises. Ever since the first outlines of preserved soft tissue were recognised in ichthyosaurs, scientists have commented on their superficial resemblance to modern cetaceans. Thanks to this new study, it seems that this resemblance goes a lot further than was previously thought.

A Close-up View of Fossilised Skin (Stenopterygius)

Picture credit: Johan Lindgren

The scientific paper: “Soft-tissue Evidence for Homeothermy and Crypsis in a Jurassic Ichthyosaur” by Johan Lindgren, Peter Sjövall, Volker Thiel, Wenxia Zheng, Shosuke Ito, Kazumasa Wakamatsu, Rolf Hauff, Benjamin P. Kear, Anders Engdahl, Carl Alwmark, Mats E. Eriksson, Martin Jarenmark, Sven Sachs, Per E. Ahlberg, Federica Marone, Takeo Kuriyama, Ola Gustafsson, Per Malmberg, Aurélien Thomen, Irene Rodríguez-Meizoso, Per Uvdal, Makoto Ojika and Mary H. Schweitzer. The paper is published in the journal Nature.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a press release from Lund University in the compilation of this article.

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment