Most Dinosaur Tongues Rooted to the Bottom of their Mouths

New research undertaken by the University of Texas at Austin in conjunction with the Chinese Academy of Sciences suggests a link between the origin of flight within the Archosauria and an increase in tongue diversity and mobility. It seems that theropod dinosaurs had tongues very similar to those of extant crocodiles, these tongues are immobile and firmly attached to the floor of the mouth.

In contrast, ornithischian (bird-hipped) dinosaurs, pterosaurs and birds may have had more mobile tongues, in the case of the volant animals, the tongue could have become adapted to serve as a device to compensate for a loss of dexterity as hands evolved into wings. For the ornithischians, their plant-eating needs could have resulted in a more mobile and dextrous tongue to assist with the processing of large quantities of coarse vegetation in the mouth, after all, most derived ornithischians unlike their Sauropodomorpha and theropod cousins chewed their food to some extent.

A Tongue-tied Dinosaur – Most Theropods Had Tongues Like Extant Crocodilians

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Comparing Hyoid Bones

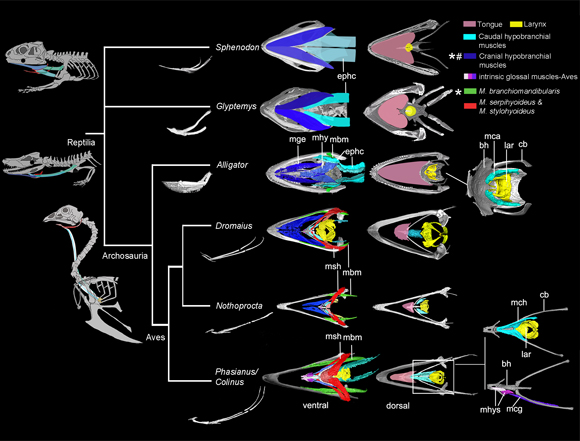

The University of Texas at Austin and Chinese Academy of Sciences researchers compared the hyoid bones of living and extinct archosaurs. The hyoid bones support and ground the tongue. In addition, to challenging how dinosaur tongues are depicted in movies such as “Jurassic Park”, the study proposes a connection between the origins of powered flight and an increase in tongue diversity and mobility.

Lead author of the research. Zhiheng Li, of the Chinese Academy of Sciences commented:

“Tongues are often overlooked but, they offer key insights into the lifestyles of extinct animals.”

Associate professor Zhiheng Li conducted the research whilst working towards his PhD at the UT Jackson School of Geosciences.

The study involved comparing the hyoid bones of extinct dinosaurs and pterosaurs with the hyoid bones of living archosaurs. The research team looked at the hyoid bones and associated muscles of alligators and modern birds. The hyoid bones act as anchors for the tongue in most animals, but in Aves (birds), these bones can extend to the tip. Comparing anatomical traits across these groups can help scientists understand the similarities and differences in tongue anatomy and how traits evolved through time and across different lineages.

The Research Team Examined Extant and Extinct Archosaurs Plus Other Groups Such as Sphenodonts

Picture credit: PLOS One

Fifteen Modern Specimens Compared to Extinct Archosaurs

High-resolution images of hyoid bones and muscles were made from fifteen modern specimens. The bird species examined included ducks and ostriches. The X-Ray Computed Tomography Facility at the Jackson School of Geosciences was used to create the images. Most of the fossil specimens used in the study came from north-eastern China (Liaoning Province), the exquisite preservation of these fossils gave the researchers the best opportunity to examine in detail images of the delicate tongue bones. The iconic Late Cretaceous dinosaur Tyrannosaurus rex was also included in this research.

The results indicate that the hyoid bones of most members of the Dinosauria, were reminiscent of extant crocodilians, the hyoid bones of dinosaurs were short, simple and connected to a tongue that was relatively immobile. Co-author of the scientific paper, published in the on-line journal PLOS One, Julia Clarke (Jackson School of Geosciences), explained that the dramatic reconstruction of dinosaurs with their tongues stretching out from between their jaws as seen in many movies, was just wrong and inaccurate.

Julia Clarke stated:

“They have been reconstructed the wrong way for a long time. In most extinct dinosaurs their tongue bones are very short and in crocodilians with similarly short hyoid bones, the tongue is totally fixed to the floor of the mouth.”

Overturning Common Misconceptions About Dinosaur Tongues

Professor Clarke is accustomed to overturning common misconceptions when it comes to dinosaurs. In 2016, Julia was one of the co-authors of a study into a Late Cretaceous bird (Vegavis iaai), the research team concluded that dinosaurs probably did not roar but may have made booming noises in a similar way to the vocalisation found in ostriches.

To read about this study: Ancient Bird Voice Box Sheds Light on the Voices of Dinosaurs.

In contrast to the short hyoid bones of crocodiles, the scientists found that pterosaurs, bird-like dinosaurs, and living birds have a great diversity in hyoid bone shapes. They think the range of shapes could be related to flight ability, or in the case of flightless birds such as ostriches and emus, evolved from an ancestor that could fly. The researchers propose that taking to the skies could have led to new ways of feeding that could be tied to diversity and mobility in tongues.

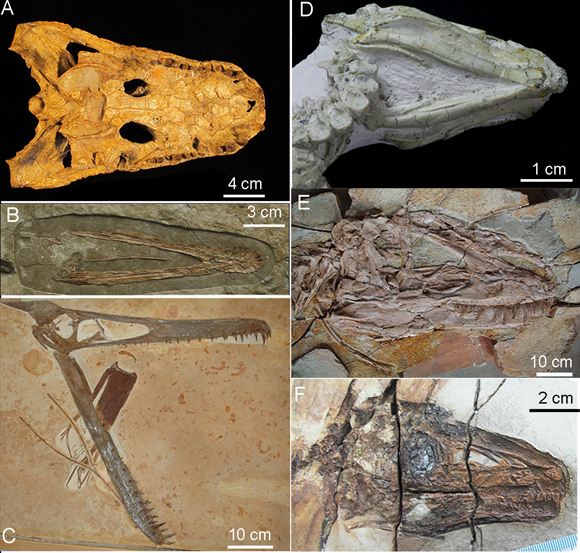

Examples of Fossilised Hyoid Bones in the Archosauria

Picture credit: PLOS One

The picture above shows a number of fossilised hyoid bones associated with extinct members of the Archosauria.

Key

(A) Alligator prenasalis, pterosaurs (B) Liaoxipterus brachycephalus and (C) Ludodactylus sibbicki, (D) basal Ornithischian Jeholosaurus shangyuanensis, (E) tyrannosaur Yutyrannus huali (F) Sinosauropteryx prima.

Professor Clarke added:

“Birds, in general, elaborate their tongue structure in remarkable ways, they are shocking.”

Co-author of the study, Zhiheng Li (Chinese Academy of Sciences), stated that the elaboration of the tongue could be related to the loss of dexterity that accompanied the evolution of flight. The tongue could have compensated for the transformation of hands into wings.

Li stated:

“If you can’t use a hand to manipulate prey, the tongue may become much more important to manipulate food. That is one of the hypotheses that we put forward.”

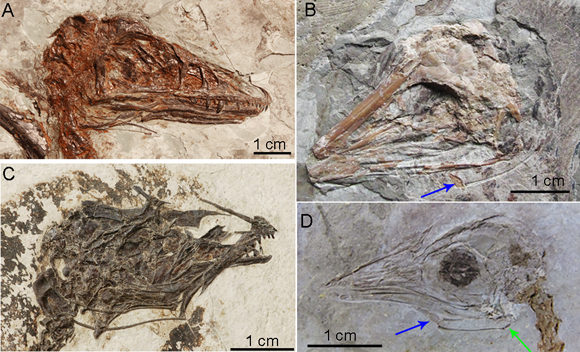

Volant Dinosaurs And Fossil Birds (Hyoid Study in Paravians)

Picture credit: PLOS One

Key

(A) Microraptor zhaoianus, (B) Confuciusornis sp., (C) Enantiornithine sp., (D) Hongshanornis longicresta. The blue arrow indicates the ossified basihyal in Confuciusornis and Hongshanornis; it was also observed in one specimen of Microraptor. The green arrow indicates the phylogenetically earliest epibranchial.

An Exception – The Ornithischia

The scientists did identify one exceptional group amongst the Dinosauria, the ornithischian dinosaurs. Derived members of this group chewed their plant food and had hyoid bones that were highly complex and more mobile, although they were structurally different from those of volant dinosaurs and pterosaurs.

Triceratops Had a Mobile and Dextrous Tongue

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The picture (above) shows a Mojo Fun Triceratops model.

To view the Mojo Fun model range: Mojo Fun Prehistoric and Extinct Model Range.

The team propose that more work needs to be done to understand the anatomical changes that occurred with shifts in tongue function. Professor Clarke commented upon how changes in the tongues of living birds are associated with changes in the position of the opening of the windpipe. These changes could in turn affect how birds vocalise and breathe.

The scientific paper: “Convergent Evolution of a Mobile Bony Tongue in Flighted Dinosaurs and Pterosaurs” by Zhiheng Li, Zhonghe Zhou and Julia A. Clarke published in PLOS One.

View the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment