How to Brood Your Eggs When You Weigh More Than a Tonne

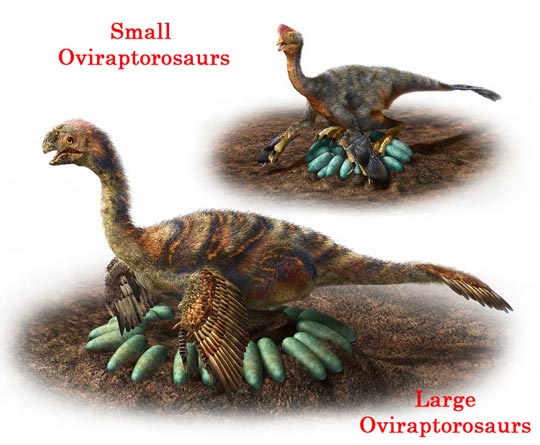

The question of how dinosaurs incubated their eggs without crushing them has been a puzzle ever since the first dinosaur nesting sites were discovered nearly a hundred years ago. A Canadian-led study has found a link between the radius of the nest of Oviraptorosauria clade members and the body size of the parent. In research into the nesting habits of oviraptorosaurs, the scientists discovered that small species laid eggs in clusters, just like many extant birds today. Much larger species, the giants such as Gigantoraptor, laid eggs in a stacked ring, so that they could keep their eggs close without crushing them with their bodies.

The Larger the Oviraptorosaur the Bigger the Nest Diameter

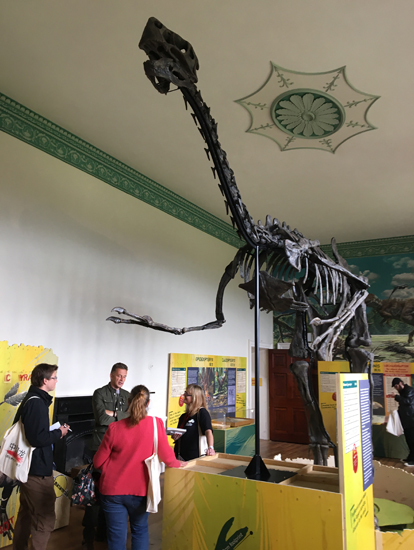

Picture credit: Masato Hattori

Dinosaurs as Dedicated Parents

Palaeontologists think that there were many different nesting strategies adopted by the diverse dinosaurs, but this study focused on the incubation of the eggs associated with oviraptorosaurs, a group of very bird-like theropods that are known from the Late Cretaceous of North America and Asia. It is very likely that these dinosaurs were dedicated parents and that they spent many weeks, incubating their eggs by sitting on the nest. How much parental care dinosaurs showed to their offspring remains an area of considerable controversy, but just like birds today, dinosaurs probably adopted a range of altricial, semi-precocial and precocial strategies* when it came to their young.

Lead author of the study, published in the Royal Society journal “Biology Letters”, Darla Zelinitsky, (Assistant Professor of Geoscience at the University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada), commented:

“In the largest oviraptorosaur clutches [Macroelongatoolithus], the central opening represents most of the total clutch area, likely allowing giant-sized species to rest their entire weight on this area so as not to crush the eggs.”

Forty Fossil Nests Studied

The research team, which included a former PhD student of Darla’s, Kohei Tanaka (Nagoya University, Japan), studied and measured around forty Oviraptorosauria fossil nests, most of which come from China, but fossils from North America and from elsewhere in Asia, were included in the study. The smallest nests revealed eggs laid in clusters, but the largest nests, associated with the largest of the oviraptorosaurs, were up to 3.3 metres wide, took on a ring shape with a large, flat, central area, presumably where the adult animal sat.

A spokesperson from Everything Dinosaur commented:

“Some of the largest nests associated with the Oviraptorosauria are so wide that a smart car could be parked in the space in the middle, the metaphor is quite appropriate given that a number of giant species have been named. Dinosaurs like the colossal caenagnathids Gigantoraptor or Beibeilong may have been much heavier than a smart car, yet it is thought that these huge animals had to sit on their nests and incubate the eggs.”

The Oogenus Macroelongatoolithus

Just like dinosaur bones, tracks and the fossilised remains of dinosaur eggs can lead to the establishment of a new genus or species. Footprints and other trace fossils that are given a formal scientific name are characterised by the epithet “ichno”, whereas, egg fossils are characterised by the epithet “oo”, the root of which is “oolithus” from the Latin meaning “stone egg”. Numerous dinosaur oogenera have been erected, one of the largest eggs Macroelongatoolithus, some of which measure sixty centimetres in length, are associated with the Oviraptorosauria.

To read Everything Dinosaur’s 2017 blog article about the establishment of a new species of giant Oviraptorosaur from embryos associated with Macroelongatoolithus eggs: Dinosaur Embryo Fossil Leads to New Dinosaur Species.

The researchers conclude that the smallest oviraptorosaurs probably sat directly on the eggs, whereas with increasing body size more weight was likely carried by the central opening, reducing or eliminating the load on the eggs and still potentially allowing for some contact during incubation in giant species. This adaptation, not seen in birds, appears to remove the body size constraints of incubation behaviour in giant oviraptorosaurs.

The Cluster Layout of Eggs Associated with a Small Oviraptorosaur

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Numerous species of Oviraptorosaurs have been named, most of these dinosaurs were relatively small around 2-3 metres in length, however, considerably larger taxa have been identified, giants such as Gigantoraptor erlianensis, which may have reached lengths of more than eight metres and weighed around 1.4 Tonnes.

While most nests have been found in Asia, in particular the Gobi Desert, Zelinitsky conducted research on dinosaur nests found in South Korea and Canada.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Zelinitsky added:

“It’s a unique structure, no other dinosaurs build their nests in that shape, and no living animals incubate their eggs this way. I just think it’s really neat that we’re able to say something more about the nesting behaviours and how they changed in these oviraptorosaur dinosaurs among the various species and species sizes.”

The researchers aren’t sure why these dinosaurs sat on their eggs. If it was to keep the eggs warm, those dinosaurs that sat in the middle of the ring probably couldn’t transfer heat as effectively as the ones that sat directly on the eggs. However, these dinosaurs had arms covered with feathers, these “wings” could have helped to shelter the eggs and to protect them as well as providing a warmer surface area to help the eggs maintain an appropriate temperature.

The researchers describe the organisation and egg layout of the nest as a “simple and elegant” solution to the problem of large dinosaurs crushing of their own eggs.

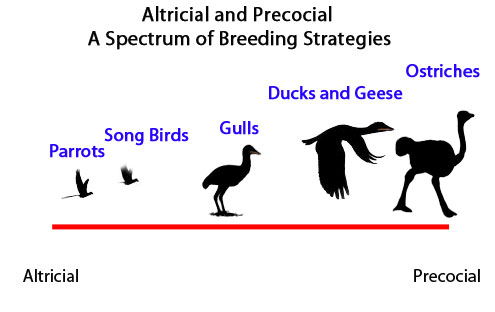

*Altricial and Precocial Nesting Behaviours

Modern birds demonstrate a variety of behavioural responses when it comes to raising their young. Some bird species like ducks and ostriches have highly precocial young. The babies are able to vacate the nest and feed themselves within just a few hours of hatching.

Other bird species have a different approach, for example, most of the passerines (song birds), such as wrens, blackbirds and thrushes are helpless when they hatch and rely on their parents to provide food and to keep them warm. In reality, the Aves (which are very closely related to the extinct oviraptorosaurs), exhibit a wide range of behaviours. Altricial and precocial traits tend to be at opposite ends of a spectrum, given the paucity of the fossil record, it is difficult to clarify the development strategy of any extinct species.

The Altricial and Precocial Nesting Behaviour Spectrum

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Visit the Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment