Researchers Get Their Claws into Citipati osmolskae

Researchers at North Carolina State University have published a paper in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B. (biology), that once again challenges the idea that organic material cannot survive the fossilisation process and persist in the fossil record for millions of years.

One of the authors of this study, Mary H. Schweitzer caused a sensation when in 2005 she claimed to have found T. rex soft tissue and proteins preserved in fossil bone. Dr Schweitzer’s research has put her at the heart of a new area of palaeontology, the search for evidence of organic remains within the fossil record.

Identifying Proteins in Dinosaur Fossils

It is another theropod that takes centre stage this time, a dinosaur called Citipati osmolskae. Citipati was a member of the Oviraptoridae, a very bird-like family of Late Cretaceous dinosaurs. A number of C. osmolskae specimens are known, including individuals found preserved along with nests of their own eggs. One such beautifully preserved specimen, MPC-D 100/979, nick-named “Big Mamma” was studied using scanning and transmission electron microscopy to identify minute details of both the fossil’s surface and its internal structure in a bid to assess whether any organic material persisted in the fossilised claws.

The Citipati osmolskae Specimen Studied “Big Mamma”

Picture credit: M. Ellison/The American Museum of Natural History

The researchers have identified tell-tale signatures that suggest the preservation (on a microscopic level), of the original keratinous claw sheath that covered its digits. This study adds to the growing body of evidence that original organic materials can be preserved over time.

A Model of Citipati osmolskae (Safari Ltd)

The Oviraptorid Citipati osmolskae

Citipati osmolskae was a theropod dinosaur that lived in what is now Mongolia during the Late Cretaceous. In 1995, a particularly well-preserved specimen of Citipati was recovered from the Djadokhta Formation of Mongolia. The specimen was found in a brooding position on a nest of eggs. It is thought that the adult and nest were rapidly buried when a sand dune collapsed on top of them.

The nearly complete remains have been beautifully preserved and it had been noted that there was a thin lens of white material extending beyond one of the bony claws on a forelimb that differed in texture and colour from both the surrounding matrix and the bone. It was also located where a claw sheath would be. At around three metres in length (mostly tail), Citipati is one of the largest oviraptorids known, it is thought to be very closely related to Oviraptor.

For models and replicas of oviraptorids including Citipati (whist stocks last): Safari Ltd. Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animal Figures.

An Illustration of a Typical Oviraptorid

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Studying the Claws of “Big Mamma”

Alison Moyer, former PhD student at North Carolina State University, who is currently a postdoctoral researcher at Drexel University and lead author of a paper describing the research, wanted to find out if the material from Citipati was a claw sheath and if so, whether any original beta-keratin had preserved.

In extant Aves, (birds), claw sheaths cover the claw at the end of a digit much like fingernails in humans. The sheaths in modern birds are composed of two types of keratin, alpha-keratin, the softer form found on the interior of the sheath; and beta-keratin, a harder and more durable keratin that comprises the sheath’s exterior. The team set out to discover whether they could detect the presence of beta-keratin.

Moyer and her university colleagues first used powerful scanning electron microscopy to assess the material. The results showed that the sample was structurally similar to claw sheaths from modern birds, so the team decided to proceed with immunohistochemical (IHC) testing, this would identify the nature of the material preserved.

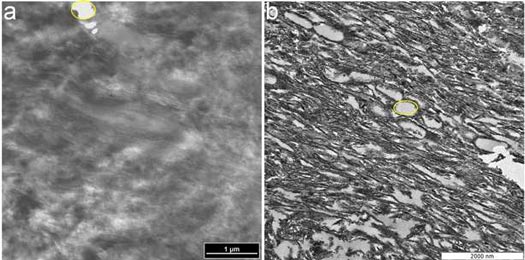

Highly Magnified Images Comparing the Internal Structure of Citipati Claw Sheath with the Internal Structure of an Ostrich Claw Sheath

Picture credit: Alison Moyer

The images above are highly magnified micrographs of (a) ostrich claw sheath and (b) Citipati claw sheath which show a similar structure. In both samples, parallel fibres can be seen running diagonally, and identical voids (yellow outlines) were observed among the fibres in both samples.

Immunohistochemical Testing (IHC)

IHC testing utilises antibodies that react against a particular protein. If the protein is present, the antibodies bind to small regions of the protein and indicate where the protein is located in the tissue. Moyer used beta-keratin antibodies derived from modern bird feathers. In initial IHC testing, results were inconclusive, which led Moyer to look more closely at the specimen. She found an unusually high concentration of calcium in the fossil claw, much higher than would be found in claws from the living birds used in comparison (such as Ostrich claw material), or from the sediment surrounding the fossil.

The team postulated that the calcium might be affecting results. The calcium was eliminated and further IHC testing on the claw sheath material was conducted. After the calcium was removed, the antibodies reacted much more strongly, indicating the presence of beta-keratin and preservation of original molecules.

Dinosaur Claw Proteins

Moyer explained:

“It’s probable the incorporation of calcium in the tissue helped preserve it, but that same calcium had to be removed in order to see the underlying molecular composition. Because this study used multiple, well-tested methods, it not only supports the longevity of proteins in the rock record, it reveals a lot about how these might be preserved.”

The researchers conclude that calcium chelation greatly increased antibody reactivity, suggesting a role for calcium in the preservation of this type of fossil material.

The scientific paper: Microscopic and Immunohistochemical Analyses of the Claw of the Nesting Dinosaur, Citipati osmolskae, Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the help of North Carolina State University in the compilation of this article.

Mineralised Blood Vessels in a Hadrosaur: Duck-billed Dinosaur Blood.

Details of a Documentary about the work of Dr Schweitzer: The Search for Dinosaur DNA.

Visit the website of Everything Dinosaur: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment