Coelacanth Gets Its Genome Unravelled

Genome Analysis Shows that the Coelacanth May Not be Too Closely Related to Tetrapods

The genome of one of the most bizarre and enigmatic of all the vertebrates known to science, the coelacanth, has been decoded revealing how this animal may have remained virtually unchanged as a species for millions of years. The data collected is also helping marine biologists and palaeontologists to understand how closely related the coelacanth group may be to the first land living animals with backbones.

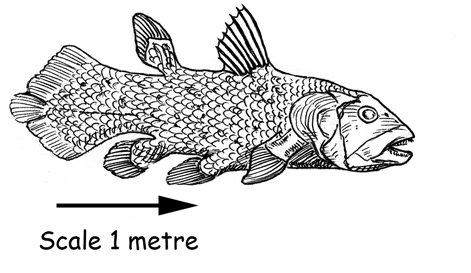

Termed a “living fossil” by many lay people, two extant species are known, one from the waters around Indonesia and a second from the Indian Ocean. The coelacanth is a member of the actinistian group of fishes, the first of these fleshy-finned fish with their distinctive tails with three lobes probably evolved in the Devonian geological period. The last of the coelacanths were believed to have become extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period, that is until one was caught by a trawler fishing off the eastern coast of South Africa in 1938.

Occasionally, specimens of these deep-water fish are caught, although marine biologists have expressed concern about the fate of this strange creature as overfishing and the development of industrial port facilities along the fringes of the Indian Ocean threatens their survival.

Coelacanth

With the genome having been sequenced, scientists are able to understand a little more about how this fish relates to other more advanced teleost fish and to also gain an insight into the evolution of land-living vertebrates, a significant moment in evolution of life on Earth as this led ultimately to the evolution of amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals and of course, our own species.

The international team of researchers including some from the Broad Institute of the MIT (Harvard, USA), from the Uppsala University (Sweden) and Washington University (United States) were able to sequence and analyse the near 3 billion protein letter combinations from the DNA of the coelacanth as well as examining the RNA from both the African and the Indonesian species. They then compared this data to the genomes of twenty other species of vertebrate as well as with typical representatives of the lungfish family. The lungfish comparison would hopefully shed light on the evolutionary origins of tetrapods – were they more closely related to actinistians (coelacanths) or dipnoans (lungfishes)?

Published in the Journal “Nature”

This study, published in the academic journal “Nature” suggests that the lungfish has more genes in common with tetrapods than the coelacanth. It can be inferred from these results that the actinistians, assuming extant coelacanths are representative of this group, are not that closely related to the first animals that dragged themselves up onto the land.

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

Coelacanth Genome

The genome of the coelacanth is also providing scientists with additional data on how gene sequences may change over time. The study suggests that some genes may evolve very slowly, this in part would help explain this prehistoric fish’s appearance, it having remained virtually unchanged for millions of years. Such a stable gene assembly may be attributed to the coelacanth’s habitat and lifestyle. It lives in relatively deep offshore waters, usually at depths of more than 300 metres. It may live in sea caves, and it is largely nocturnal moving little during the day and then hunting at night. The very uniform environment and an absence of other fish species competing for this particular niche in the offshore ecosystem may explain why the coelacanth has had little need to change and evolve over vast periods of time.

The international team of scientists admit there is much more to learn about the transition of vertebrates from water onto the land. However, the lungfish genome represents more of a challenge than that of the coelacanth. Although collecting specimens of lungfish is easier, after all, extant lungfish are all freshwater fishes, making them theoretically easier to collect, the lungfish genome is much larger, estimated to exceed 100 billion letters (C G A T), in length. The more modestly sized genome of the extant coelacanth is permitting scientists to study changes that may have helped the first tetrapods to adapt to a terrestrial habitat. Comparisons with tetrapods had led the researchers to isolate chains of genes that regulate and control other portions of the sequence, these studied in conjunction with an analysis of what genes are present in the coelacanth but absent in tetrapods has enabled some startling insights to be made.

Identifyin Differences Between the Coelacanth and Tetrapods

A number of immune-related regulatory differences have been identified between coelacanths and land-living animals. The scientists have postulated that these changes reflect adaptations as a result to new pathogens the first tetrapods encountered as semi-aquatic vertebrates. Other differences in the genomes provide clues to sensory development, senses such as a lateral line in a fish is not much use to a creature that lives on land. Genes involved in smell perception and detecting airborne odours have been identified as a result of this research.

Similarities in genetic material have also been found between the marine coelacanth and animals that live entirely on land. the HoxD strand of genetic material is common between coelacanths and tetrapods. It is likely that this particular strand of genetic material was a prerequisite to enable the first land animals to develop hands and feet, to assist with locomotion, but as tetrapods evolved and became more specialised, this region of genetic material played a role in the evolution of our own dexterous, tool wielding hands.

Coelacanth Model

Safari Ltd have produced a model of a coelacanth, it forms part of the company’s Wild Safari Dinos & Prehistoric Life model series. The model measures fifteen centimetres in length approximately and is a fine example of a replica of a lobe-finned fish. Not only has this model been popular with collectors but it has also proved to be very useful for schools and home educators who have used this model in teaching topics on evolution and life on Earth.

To view the range of prehistoric animal figures: Safari Ltd. Models of Prehistoric Creatures.

One of the more unusual puzzles concerning the move to a terrestrial existence was the way in which waste products from the body were excreted. Fish excrete ammonia into the water, this gets rid of waste nitrogen. Land animals evolved a method of converting ammonia into the less toxic urea – the urea cycle, whereby ammonia is converted to the more inert urea, or uric acid. If ammonia is allowed to build up in cells it will prove toxic to the cell, the researchers found that the most important gene involved in the regulation and control of urea or uric acid production had been modified and was present in tetrapods.

Commenting on the study, Chris Amemiya (Professor at the University of Washington), stated:

“This is just the beginning of many analyses on what the coelacanth can teach us about the emergence of land vertebrates, including humans, and, combined with modern empirical approaches, can lend insights into the mechanisms that have contributed to major evolutionary innovations.”

An International Research Project

This research project brought together a number of institutes and universities, it was a truly international effort, and it is hoped that the publishing of the genome will help to raise the profile of conservation efforts to help ensure the survival of the coelacanth. A second team of scientists, a joint expedition from the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity and the French National Museum of Natural History set out earlier this month to explore the sea cave home of a population of coelacanths living in the Sodwana Bay area (off the coast of South Africa). By studying the coelacanth in its natural habitat, the scientists hope to learn more about how these strange creatures use their fleshy fins for locomotion and how they hunt and what prey animals are their preferred food.

To read more about this expedition: Scientists Set Off in Search of the Lair of the Coelacanth.

The scientists responsible for the genome research, acknowledge the importance of their work but also recognise that there is a lot more to learn when it comes to this “living fossil”. Future studies will help to shed further light on that very significant period in the history of life on Earth when vertebrates first moved onto land.