Did the Ancient Rhynchocephalians Out Compete Early Mammaliaforms?

Had you been around south Wales or south-western England some 200 million years ago, you would most probably have required a boat to get about. The area around the Bristol channel today (where you still need a boat), during the Early Jurassic, consisted of a series of small islands surrounded by a warm, shallow tropical sea. This archipelago (referred to as the Mendip Archipelago), was home to small dinosaurs and also to a variety of other reptiles including five species of Clevosaurus.

Studying Clevosaurus

Clevosaurs are members of an ancient Order of reptiles called the Rhynchocephalia. A new study published in the journal of the Palaeontological Association, suggests that these hardy reptiles may have filled the roles performed by early mammaliaforms on some of these small islands.

In addition, where Clevosaurus fossils are found, mammaliaform fossils tend to be lacking, so did these two types of tetrapod compete with each other for the same food resources? This new research carried out by members of the School of Earth Sciences (University of Bristol), indicates that this could have been the case. The scientists examined the biomechanics of the skulls of these lizard-like reptiles in a bid to gain an understanding of the likely diets of the species studied.

Different species of clevosaur had different bite forces, which hints at a degree of niche partitioning within this genus. This may explain why five different species were able to exist within a relatively small area.

Different Species of Clevosaurus may have had Slightly Different Diets

Picture credit: Sofia Chambi-Trowell (University of Bristol)

Computerised Tomography Used to Analyse Skull Biomechanics

PhD student, Sofia Chambi-Trowell, from Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences, worked on CT scanned skulls of ancient rhynchocephalians and found differences in their jaws and teeth.

The student commented:

“I looked at skulls of two closely related species of Clevosaurus, Clevosaurus hudsoni and the slightly smaller Clevosaurus cambrica – the first one came from a limestone quarry near Bristol and the other one from South Wales. Clevosaurus was a lizard-like reptile, but its teeth occluded precisely, meaning they fit together perfectly when it was feeding. But what was it eating?”

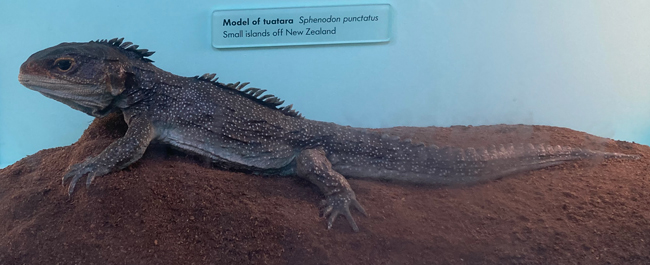

Rhynochocephalians (beak heads), were a very successful, globally distributed group of diapsid reptiles that flourished during the Mesozoic. The Tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus), is the only living member of this order, the Tuatara is confined to small islands off the coast of New Zealand and some specially designated and protected release sites on North Island.

Using Finite Element Analysis

Whilst studying the extant Tuatara is of great assistance to palaeontologists, expanding any findings to extinct members of this group is challenging. Likewise, identifying the feeding habits of long extinct species is equally difficult. However, finite element analysis conducted on two, near complete, three-dimensionally preserved skulls (Clevosaurus hudsoni and Clevosaurus cambrica respectively), provided bite force data and an assessment of jaw biometrics. From this information, the potential feeding preferences of these two closely related reptiles could be inferred.

The Last of the Rhynochocephalians – A Tuatara

Picture credit: Everything Dinosaur

The researchers found that Clevosaurus had bite forces and pressures sufficient to break down beetles, and even small vertebrates easily, suggesting they could have taken the same prey items as the early mammals on the islands. Calculations of muscle forces show that Clevosaurus hudsoni could take larger and tougher prey than the more slender jaws of Clevosaurus cambrica.

Did Clevosaurus Compete with the World’s First Mammals?

Co-author of the scientific paper and the project supervisor, Professor Emily Rayfield (University of Bristol) stated:

“We wanted to know how Clevosaurus interacted with the world’s first mammals, which lived on the Bristol islands at the same time. I had studied their jaw mechanics a few years ago and found they had similar diets and that some fed on tough insects, others on softer insects.”

This study, having identified difference in jaw mechanics between different species of Clevosaurus provides a hypothesis as to why several species of Clevosaurus could co-exist in the same habitat. Niche partitioning could have been taking place with each species avoiding competition by specialising in hunting and eating different types of prey.

As the data generated in this study is roughly comparable to what is known about the jaws of early mammaliaforms, it raises the intriguing prospect that the jaws may have been functionally similar and thus rhynochocephalians and early mammaliaforms were in direct competition with each other for food resources.

Everything Dinosaur acknowledges the assistance of a media release from the University of Bristol in the compilation of this article.

The scientific paper: “Biomechanical properties of the jaws of two species of Clevosaurus and a reanalysis of rhynchocephalian dentary morphospace” by Sofia A. V. Chambi‐Trowell, David I. Whiteside, Michael J. Benton and Emily J. Rayfield published in Palaeontology.

The award-winning Everything Dinosaur website: Everything Dinosaur.

Leave A Comment