Don’t Climb a Tree to Avoid a Marsupial Lion

Thylacoleo carnifex Behaviour Deduced from Cave Claw Mark Study

Don’t climb a tree in a bid to avoid an attack from a Marsupial Lion (Thylacoleo carnifex). That might have proved very good advice to the first inhabitants of Australia who set foot on the continent some 50,000 years ago. These early explorers would have encountered a bizarre and unique fauna dominated by giant monitor lizards, flightless birds and strange mammals, the like of which existed nowhere else on Earth.

Thylacoleo carnifex

One of the more peculiar creatures, and an animal probably best given a wide berth, was the leopard sized Marsupial Lion (T. carnifex). The name “Marsupial Lion” for an animal about the size of a male African leopard (Panthera pardus pardus), albeit slightly heavier, may sound like a bit of a misnomer, but from a palaeontological perspective this is just one of the peculiarities surrounding this enigmatic creature.

Thylacoleo carnifex – Study Suggests These Marsupials were Capable Climbers

Picture credit: Peter Trusler/Australian Post

However, a new study assessing scratches and claw marks left in the main cavern of Tight Entrance Cave, located in south-western Australia, has provided fresh insights into the likely behaviour and habits of these prehistoric animals. This new research suggests that Thylacoleo carnifex was an able climber and that it probably raised its young in caves.

A Chequered History

The habits and diet of the Marsupial Lion has puzzled scientists, almost since the initial scientific description by Richard Owen (later Sir Richard Owen), in 1859. At first, this animal was thought to be a carnivore, but as a member of the Order Diprotodontia along with kangaroos, it was then suggested to have been herbivorous.

Anatomical analysis reveals Thylacoleo to be a robust animal with strong back legs and powerful shoulders, not particularly adept at running. It had been thought that this animal filled the ecological niche occupied by bears outside Australia. Recently, the idea that the Marsupial Lion was an apex predator that could drag prey up into trees became popularised. Thylacoleo as a sort of Aussie version of a leopard was even illustrated on the front cover the prestigious magazine Prehistoric Times.

Prehistoric Times Featured Thylacoleo (Issue 85)

Picture credit: Prehistoric Times

A Tree Climber?

Scientists from Flinders University (South Australia) analysed the scratch marks left on the walls of the main chamber in the Tight Entrance Cave. The majority of these marks were clustered on a near-vertical rock face that led up towards an exit to the surface. That exit may be blocked today, but clearly this way out of the cave was a preferred route for many Marsupial Lions rather than using a circuitous path with a lesser gradient.

This suggests that these animals were confident and assured climbers and remarkably agile. In addition, the study indicates that the scratches were mostly made by juveniles, this suggests that Marsupial Lions may have reared their young inside caves.

One of the authors of the research, published in the open access journal “Scientific Reports”, Associate Professor Gavin Prideaux (School of Biological Sciences, Flinders University) commented:

“Our findings indicate the Marsupial Lions were running up and down these rock piles to get out of the cave, and they weren’t using the lower-gradient, longer route. We can be confident now and say that they could climb and if they could climb really well in the dark, underground, there’s no reason they couldn’t climb trees.”

Marks Made by Juvenile Marsupial Lions

In order to confirm that the scratches were most probably made by juvenile Marsupial Lions, co-author Samuel Arman, established a list of seven potential candidates, composed of both living and extinct species. A model was made of a Thylacoleo paw to test how the digit and claw configuration matched against the scratch marks from the cave. To assess the sort of claw marks made by extant animals included in the study (possums, wombats and Tasmanian devils), scratch pads were given to zoos so that they could be placed inside the enclosures where these animals were housed. Any claw markings were examined and cross referenced against the trace fossils from the cave.

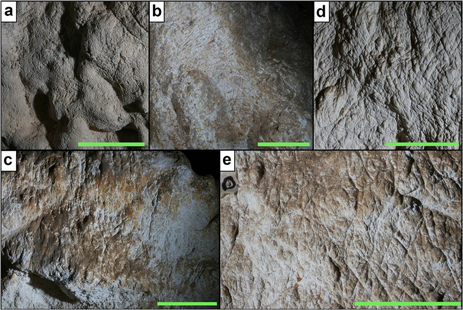

Examples of Scratch Marks from the Cave

Picture credit: Flinders University/Scientific Reports

The picture above shows (a) cave wall south, (b) marks from a central rock pile to the west, (c) marks from a central rock pile from the south sub-region of the main cavern, (d and e) scratches from the boulder sub-region. Scale bar = 10 cm.

Based on this research, it seems that climbing a tree to avoid the attentions of Thylacoleo would not have been a very good idea.

The Ubiquitous Marsupial

The various eclectic theories regarding the habits of T. carnifex that have been proposed may have had something to do with the wealth of fossil material available to study. More complete or partial skeletons of Marsupial Lions are known from cave sites than for any other extinct Pleistocene species. Thylacoleo carnifex is amongst the best represented large carnivores known from Pleistocene fossil bearing sites.

For models and replicas of prehistoric mammals: CollectA Deluxe Prehistoric Life.